Ed Reimard: 'Don't Look Back'

Ed Reimard: 'Don't Look Back' Ed Reimard: 'Don't Look Back'

Ed Reimard: 'Don't Look Back'by Michael Kube-McDowell

originally published in the South Bend Tribune's Sunday

magazine Michiana, August 28, 1983

Ed Reimard: A Life of Adventure

Sidebar: Ed Reimard the Barnstormer

The invasion of Saipan. Treasure-diving in the Bahamas. Barnstorming in Pennsylvania. Some might call them adventures. Goshen's Ed Reimard, who experienced all three, calls them old hat.

"I'm a great one for when things are over, they're over," said Reimard. "Yesterday is a canceled check, today is ready cash, and tomorrow's a promissory note."

But it's more a reluctance to brag or bore than a failure to appreciate what life steered his way that keeps Reimard looking forward.

"It was beautiful, and don't think I don't reminisce a lot. Lord God, I've lived in the most interesting era, from the horse to the rocket--and was involved in a lot of it, from flying to diving," he said.

But Reimard almost never got out of his hometown of Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania. Struck by a car while a youth, he suffered enough broken bones and other injuries ("I had the top of my head ripped off") that he was not expected to live.

"I hadn't died after three days so my uncle, who was head surgeon at Mercy Hospital in Wilkes-Barre, came down to see what he could do. I had to spend six months in a body cast, and then when we took the cast off we found out the back was fractured," he recalled.

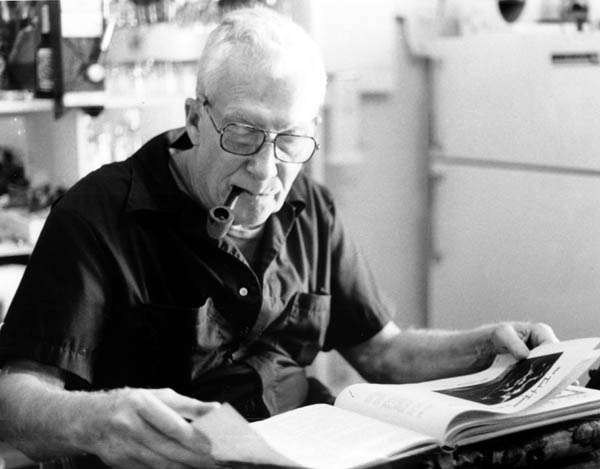

Reimard stands straight and lean now at 63, and lives in a small neatly-kept home on Goshen's north side with his wife Peg. The Reimards moved to the area in 1974 to be near daughters Nancy Wiese and Barbara Garvin. Another daughter, Sally, lives in Wisconsin, while son Bob has made a career of the Air Force.

Though the spine is still kinked from the untreated triple fracture, Reimard has never let his injuries keep him from anything he really wanted to do. "It's been a problem over the years, but when you have something like that that nothing can be done about, you grin and bear it," he said.

But the injury made it hard for Reimard, who felt that "a country worth living in is worth fighting for," to sign on with the armed forces during World War II. Recruiters took one look at his application and said no thanks.

"I was married and had three kids, and I had a 3-C classification because I was running the experimental welding department at the American Car and Foundry," he explained. "I'd get a release every once and a while and enlist. I got in the Seabees one time and got as far as Philadelphia before I was sent home. I flunked out three times physically and finally lied like crazy and got in."

His Navy training at Bainbridge, Maryland lasted just three weeks, after which he found himself headed west, to Pearl Harbor, and the Pacific theater. His assignment: welder on an "auxiliary to Invasion" named the Niobrara, a fleet oiler loaded with 160-octane airplane fuel, black oil, and diesel oil.

At Pearl Harbor, he signed up for Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) training, thinking "I could go to school for anything if I could get off this aux to invasion." But nothing came of it until the Niobrara reached Kwajalein, when Reimard and a shipmate found themselves temporarily transferred to a UDT ship for training.

"They had a 100-foot tube there that we went down and came up with a Momsen lung. It was a very short course, and as far as scuba gear is concerned I never saw it until I got back to the States. Not even flippers. It was just a case that if you were a good swimmer, you qualified," Reimard said.

Then it was back to the Niobrara and welding, until June 1944, and the invasion of Saipan in the Mariana Islands. Saipan was protected by coral reefs and by mines and barriers placed on them by the Japanese. The full-time UDT teams were charged with mapping safe paths through the reefs for the first wave of invasion boats.

The part-timers, Reimard among them, were tabbed to plant explosives to clear a channel through the reef so larger boats could bring supplies and reinforcements.

"We figured we'd never be used, but they called two of us off the Niobrara. They used us that day and that day only. It wasn't a great coordinated affair, as far as I was concerned--very little preparation," Reimard says.

"Our gear consisted of a pair of shorts and a demolition pack. They went through with a whaleboat and said, "We'll be back here in two minutes to pick you up, be here.' So we went down, fastened the demo pack. There was a lever on it that you just turned after you fastened it, you got the hell out of there, and the reef blew. They said it was very successful. As far as I was concerned, it was, because we got out of it."

A decade later, Reimard found himself descending beneath another ocean for another reason: the lure of sunken treasure.

"I went to Bermuda in the early 50's, where I met Teddy Tucker and Dr. Mendel Peterson of the Smithsonian," remembered Reimard. "I was supposed to go fishing with Tucker, and called him up. He said 'Well, why don't you go along with us, I'm working with these people from the Smithsonian.'

"I said, 'Good, I'll get some pictures.' I was kind of a bug on photography, and so I went along, and it wasn't long before I had a suit on and was down looking the situation over."

Before the year was out, Reimard had diving gear and underwater cameras of his own. Through the late sixties, he was to split his time between his camera shop in Pennsylvania and the Smithsonian's largely volunteer "Glub Club," led by self-taught underwater archaeologist Peterson.

"It wasn't a full-time job, I'd work with them maybe a week, ten days at a time. They would fly me to wherever the project was--no pay, the Smithsonian doesn't have money for things like that--but they'd wine you and dine you well, and pay my expenses there," Reimard explained.

"Pete and his crew was brought in to substantiate shipwrecks and photograph the various artifacts, not necessarily gold coins and silver coins, but to substantiate the various ship fittings and so on. Of course, we got to see the treasure, too, because that was the most sensational part of it."

Reimard learned quickly that the popular conception of treasure hunting was more fantasy than fact.

"Everybody thinks of a sunken ship with sails flapping in the waves, sitting on the floor of the ocean just waiting to be plundered, when actually what you see at a shipwreck is some ballast stones, old cannon, an anchor or two, and that's all that's left," Reimard says. "You don't find anything of an old wooden ship that's above the mud, because the teredo worms clean that up in very short order."

The treasure hunters and undersea explorers Reimard knew and worked with constitute a "Who's Who" of the field through the 1950's and 1960's. Among them are Art McKee, who began in the "hard-hat" days of diving and collected enough artifacts to open his own museum; Tom Gurr, who found treasure at sea and trouble in the courts; and Ed Link, a pioneer in the development of small submersibles.

But Peterson and Tucker continued to be Reimard's strongest connection to the treasure-hunter's world. As Curator of Naval History for the Smithsonian and through his work along the Florida coast and around Bermuda, Peterson came to be recognized as one of the leading authorities on New World wrecks. Reimard worked with him over a span of nine years, and is proud to be listed along with Gurr and McKee on the Acknowledgments page of Peterson's book "Funnel of Gold."

Reimard's relationship with Teddy Tucker lasted even longer, spanning a dozen years and many wrecks. Tucker has earned the nickname "Mr. Treasure" for his discoveries in the waters around his home island of Bermuda. The most spectacular of those finds came in 1955, when he plucked a 350-year old gold and emerald cross from a Bermuda reef.

"It was the most valuable piece of jewelry ever to come out of the bottom of the ocean--you have to see it to really appreciate it," said Reimard. "Absolutely one of the most fascinating pieces of Jewelry you ever laid eyes on. The workmanship was tremendous, beautiful. Words can't express--I've handled it, and it's just amazing."

Every wreck Reimard worked has its own history and its own stories. He tosses out one name after another: the HMS Warrick, the Blanche King, the San Pedro, the Pelonation.

"The first one I worked was the old Constellation, the last four-masted schooner to leave the States for South America with general cargo--1942. It went on the reefs in Bermuda and sunk. And then we worked an old 16th-century paddlewheel which was unidentified, and that was where I got my set of crucibles for melting precious metals. It took me three years to get the whole set," said Reimard.

Other wrecks yielded other memorabilia: from one, a padlock encrusted with coral and shells. From another, an assortment of sailmaker's palms, metal disks sewed into gloves and used as thimbles.

"Over the years, I've given them away to where 1 don't even have one," he admitted with regret.

Mounted in the masonry of the Reimards' fireplace is another memento: a grindstone recovered from the 1717 wreck of the English merchantman Caesar. Reimard calls the grindstone "one of the smallest of the small," and many of the larger ones remain on the bottom near Bermuda.

"One extremely amazing thing which we found was a six-foot crossbow. It fired a six-foot shaft, and it had two big arms with two big balls on them, and the track in the center," says Reimard. "There was no history whatsoever of there being such a thing, but we found two of them on an old 15th century wreck off Bermuda. To the best of my knowledge, one is still down there, because the one we brought up was too far gone to do anything with so we left the other one down there."

That was not the only time Reimard encountered the slow, steady destructive power of the sea.

"On the Warrick, we uncovered a musket and a saber which after they were uncovered completely disintegrated, they were so badly decomposed," Reimard recalls. "We worked very meticulously to uncover it, and finally one piece of it broke loose, and when that did the whole thing just fell apart and went up the airlift. I didn't even get a picture of it before it disintegrated."

Silver coins were frequently found welded together in stacks or lumps, converted by the sea's chemistry into silver pseudomorph. Gold fares better, the calcium which makes up human bones more poorly--fish eat it.

Of all the wrecks Reimard came to know, the San Jose stands out as the most memorable, for a combination of personal, historical, and legal reasons.

"I spent so much time on her over a two and a half year period," Reimard said. "I would go down there for a week or ten days, come back for a month or so, then go back and pick up on the progress of it."

The San Jose de las Animas was part of the 22-ship Nueva Espana Flota which set sail from Havana for Spain in the summer of 1733. Included in its cargo were more than 30,000 pesos in silver, a small part of the plunder from Mexican mines being transported by the 1733 plate fleet.

But just one day out of port, the Nueva Espana Flota ran afoul of hurricane-strength winds. By nightfall of the second day, the entire fleet was wrecked, scattered along the Florida coast from Key Biscayne to Vaca Key. Spanish salvors refloated a number of ships and burned fifteen others to the waterline, the San Jose among them, when salvage operations were complete. Most of the treasure and much of the other cargo was recovered.

The remains of the San Jose lay undisturbed until the summer of 1968, when treasure-hunter Tom Gurr and his team discovered them off of Rodriguez Key. Gurr called Mendel Peterson, and from the first day of digging, the treasure hunters and the authenticators worked side by side.

"It was thirty feet to the sand, and then we excavated down to about 48 feet. It was completely buried, there was nothing visible," Reimard remembered.

Working in two hour shifts with "no safety vest, no wet suit, no nothing, just a weight belt to keep you down there, and a Desco mask to give you air," the divers uncovered silver coins, unbroken olive bottles, oddities such as a glass cat from the Orient and a wood cartridge belt, and of course, cannon.

"This is the crazy thing about cannons, you'd think they'd be valuable, but most of them were never brought up. There were 68 supposed to be aboard the San Jose, and we found 38 of them, but only a few were ever brought up," said Reimard.

But one modern pirate thought enough of the cannon to steal two of them off the bottom. The case ended up in court, and film shot by Reimard was a turning point.

"The day we found the cannon, I went down and as they were uncovered I took movies of them. The first thing Tom started to do was go after the trunnion pins, to find the moldmakers marks," said Reimard. "Of course, knocking the coral off with a hammer left some hammer marks. In court, the case was, "Who can prove that these are the cannon?' So I sent my movie film, and the marks where the hammer hit were visible on the cannon, and that's what cinched the case."

The most unusual find came as the excavation neared the 48 foot level: an intact 250-year old skeleton, the only one ever found on an 18th-century wreck.

"We found what we called 'our boy Pedro' down in the bowels of the ship. We found one and a half skeletons, and according to history there was two people lost on her. He was down right next to the keelson, and with him was a cache of 18 little gold rings," said Reimard.

Pedro's rings and the other treasure attracted the attention of the State of Florida, which claimed ownership of the wreck and everything on it, even though it lay outside the three-mile limit in effect at that time. On one occasion, state agents attempting to board the salvage ship Parker were fired on by Gurr's crew. Later, Customs agents armed with Thompson submachine guns and backed up by a Coast Guard cutter searched the Parker, and Gurr Was ordered by a Florida court to turn over all the items recovered from the San Jose.

To end the court battles, Gurr was forced to agree to a contract with the state which would give his team a 25% share of the find instead of the customary 50%. But even then, the state delayed paying Gurr his share for five years, driving him to the brink of bankruptcy. At one point, the Parker sank at dockside in Marathon because Gurr couldn't afford to keep someone aboard to mind the bilge pumps.

Finally, with a CBS camera crew recording the action, Gurr returned to the wreck site in a 17-foot boat and, rather than give them to the state, dumped what artifacts he still had back into the ocean. Eventually Gurr was charged with grand larceny.

"Tom was extremely honest on the whole operation, but the state basically crucified him," Reimard said.

Though the U. S. Supreme Court eventually overruled Florida's claim to the wreck, by that time Gurr had run afoul of the Securities and Exchange Commission for selling too many shares of the find to investors.

"It kind of ended up a little illegal. A lot of people lost a lot of money, because the state confiscated everything," Reimard said.

Almost everything, that is. Among the exceptions was one of Pedro's gold rings, which Reimard describes as "sixty-eight cents worth of gold that the State of Florida valued at $800 apiece." Reimard knows all about the elusive ring, because he knew where it was.

"The state had 17 of the 18 and I had the other one. Of course, the state knew I had one, but they couldn't do anything about it because it was out of the state before the injunction was put on," Reimard said with a smile. "My son has it now."

But despite all he's seen and done, and despite the obvious pleasure Its given him, Reimard remains modest to a fault. Reluctant to talk at all, when persuaded he talks more freely about Peterson and Tucker, the Niobrara and the San Jose, than about his own part in the events of his life.

Reimard speaks with pride of his son: "He's a fine lad, smart, he's got a pile of beautiful citations from every base he's ever been on." He speaks with love of Peg: "She's been an excellent, excellent wife." But on the subject of Ed Reimard, he has little to say.

"I don't go around bragging about these things," he demurs. "I just happened to be in the right place at the right time."

Even before Ed Reimard became hooked on the secrets of the sea, there were signs that he was not going to be content spending his life glued to Mother Earth.

"As a real young lad, I used to go down to the airport Saturdays and scrub grease pans for a ride around the field in an old Waco or Fleet. The first job I ever had was working for Woolworth's, ten cents an hour ten hours a day, sitting in there building model airplanes," he recalled. "I had the bug for years."

When Reimard was a teenager, he and a friend bought a used Aeronca "Air Knocker" for $250. Though the only lessons he took were informal ones from the former owner, he chalked up more than 50 hours flying time. After World War II, it took him less than a week to earn a license.

"I started on a Monday noon, flying an hour a day, and soloed Friday. I think I had five hours when I soloed," said Reimard.

For the most part, he found himself flying surplus military training planes such as the Fairchild PT-17 and PT-19 and the Piper L-4. Eventually he tied in with the Civil Air Patrol, flying an L-4 on search and rescue missions and serving as assistant communications officer for Pennsylvania. But most of his memories come from the dying days of barnstorming.

"In order to draw a crowd at the airport, we'd take the PT-19 or 26 and go up and start rolling around. We'd watch the field, and when we'd get a crowd gathered then we'd go down and hop passengers," he said. "Afterwards we'd fly home. We only did this on the weekends, the only time you could draw a crowd."

A painting of a PT-19 hung in Ed Reimard's kitchen. |

For the fun-proof modern private planes and the "electonic ride" of jets, Reimard has nothing but scorn. But he retains an affection for the aircraft of the 30's and 40's, and pictures of several of them hang in his kitchen.

"It's funny what you could do with the old stuff that you just can't begin to do today. One maneuver I used to like which was always a crowd pleaser was an inverted spin," Reimard said. "You'd pull it up into a loop, and then you'd put forward pressure on the stick and take it upside down. When she finally stalls, she just starts to fall, and she may come down tail first, or slide off on one wing. You need close to 2000 feet to clear out, because you don't know where it's going to go and you have to pick up flying speed before you can control it."

Flying aging planes under such circumstances, accidents and near-accidents were inevitable, and Reimard had his share. But as he says, "I never had any bad accidents. I walked away from every one. Oh, I had close ones, lots of them. Doing air shows I would do things that would get me in trouble."

On one occasion, while climbing straight up in a PT-19, he had a moment of indecision about what to do next.

"In the PT-19, you get in a position like that, why, the engine would shut off, it couldn't get gas. This particular day I didn't make my mind up soon enough. I was going to kick it over forward, and at the last moment I thought, `No, I'll roll out on top.' I pulled her back, and she was already stopped, the engine had quit, and she started to back down."

Fearful that the whip stall might tear the engine loose, and mindful of the parachute he was wearing, Reimard stood up in the cockpit and prepared to jump."Then I looked down and said, `Whoop, I don't think so.' And then I had the devil of a time getting back in. I had to kick a foot through the fabric and pull myself down, and by that time she'd started to roll over, nose down instead of the tail. I made a pass over the parked cars and the people were all flicking their lights and blowing their horns, it was a wonderful show for them, but I wanted to get on the ground after that," said Reimard.

A stalled engine also figured in an episode when Reimard was going to visit his parents on their farm near Benton, Pennsylvania.

"I used to go up Sunday mornings and I'd buzz the farm, I'd rattle the dishes in the cupboard when I'd come in over the house, and then I'd go over and land at the Benton airport. This day I very lazily buzzed the house and pulled up and turned my head to look back and see if my dad came out and waved, which meant he'd come up to the airport and pick me up. As I pulled up, I reached over to throttle back, and instead of grabbing the throttle I grabbed the mixture control. And the engine went `ptchew fsssh.' And I thought, oh no."

With the engine stilled and the airport out of reach, Reimard headed for the Sunday-morning stillness of the main street of Benton.

"There wasn't too many people on the street, and I could clip the wings on the trees and telephone poles on the edge and save the fuselage and me. As I was settling down about 200 feet off of the street, I noticed the throttle was on full and the mixture was on lean," he said.

With the controls reset, he tried to restart the engine."It caught, and I went across the town of Benton at about 150 feet off the ground, Sunday morning. I immediately went back to Bloomsberg, but when I got there there was two state police cars parked at the apron, and needless to say I got quite a talking to. But the flight instructor explained to them that I was extremely lucky to recover from it, because that had killed an awful lot of people. It was almost a disaster, and I was shook so bad I sat there on the taxiway for about 15 minutes before I could get out," said Reimard.

But in the end, it was the greying of the aircraft rather than his own misadventures that ended Reimard's flying days. Airframes designed in the 1930's and built in the 1940's were being weakened by the stress of flight and by such gremlins as hidden leaks from gas tanks.

"That's the reason I finally quit, because most of the aircraft that I loved to fly had just gotten to the point where you didn't know if they were going to fall apart," he said. "The center sections would rot out, and back in those years, there was a lot of those things crashing when it wasn't the fault of the pilot. I figured the law of averages had about come up."

Update: Edward F. Reimard passed away on 18 May 1996, in Goshen, Indiana, at the age of 75.

![]() Return to

K-Mac's Nonfiction Library.

Return to

K-Mac's Nonfiction Library.

Last Revised: May 21, 2009