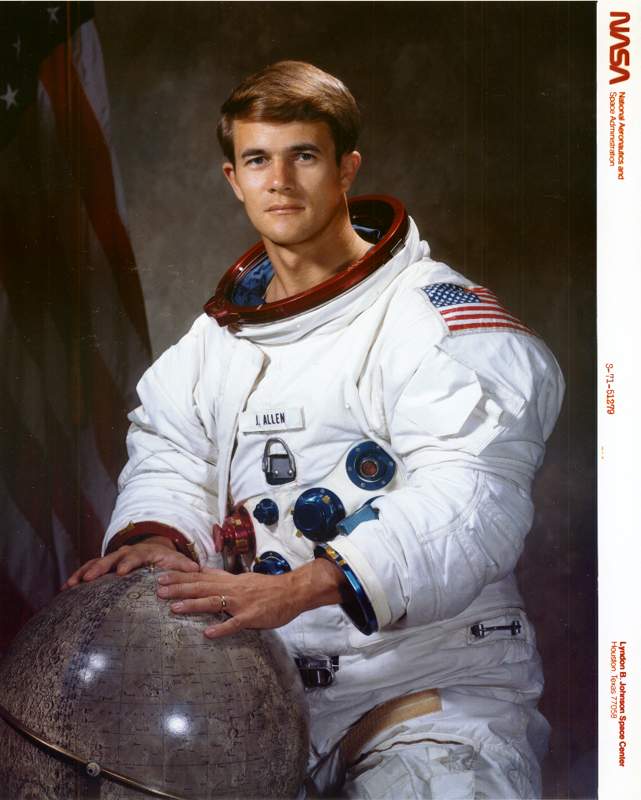

Space Rookie Joe Allen Looks Forward to STS-5

By MICHAEL KUBE-McDOWELL

first published in The Elkhart Truth, October 11-12, 1982

Part One: Columbia Flight of Special Note to Elkhartans

Part Two:

Space Rookie Tells of Goals

Though some people may see the fifth flight of Columbia in November as just another space shuttle launch, you can be sure that astronaut Joe Allen and his Elkhart-area friends and relatives won't be among them.

For Allen, a Crawfordsville native, and William Lenoir, his fellow mission specialist, the mission means the end of a 15-year wait to get into space.

Though Allen will be too busy for much celebration, his relatives and friends will be doing their best to pick up the slack. Among them will be Allen's mother-in-law, Mildred V. Darling, of Elkhart.

Like many of NASA's older astronauts, Allen was grounded by the cutback of the Apollo moon project and the virtual collapse of the manned space program in the years following.

Consequently, 18 months ago, Allen talked like a man trying to convince himself he'd made the right job choice.

"It's not as though I feel today there's been a promise broken," he said then. "The fact that I have not made a space mission, and in fact may never make a space mission, does not mean that the job day-to-day is not interesting."

But Allen no longer has to be good-naturedly philosophical.

"Maybe you don't really know for sure until the solid rockets light off," he said in an interview with The Truth. "I'd been increasingly hopeful for the last year that it might work out."

Allen and Lenoir were among 11

scientist-astronauts selected in August 1967. Before applying to

NASA, Allen conducted research in nuclear physics at the

University of Washington. He has a doctorate in physics from

Yale.

Allen and Lenoir were among 11

scientist-astronauts selected in August 1967. Before applying to

NASA, Allen conducted research in nuclear physics at the

University of Washington. He has a doctorate in physics from

Yale.

"I was at a point in my career where it didn't cost much to try," Allen said. "I did it as much out of curiosity as anything, and one thing led to another."

Four of those selected with Allen have since resigned. He and Lenoir are the first of the group to receive a flight assignment.

Mrs. Darling, mother of his wife, Bonnie Jo, is more effusive about the upcoming flight.

"I'm thrilled about it, thrilled to death," Mrs. Darling said. "He's waited so long for this. "He was beginning to think he wouldn't get to go."

"I don't think I ever thought about space travel until it came up that he was going to be an astronaut," Mrs. Darling said. "Then I thought, 'Well, I'm not too happy about this."'

But such thoughts are long gone. When Allen was capsule communicator for the Apollo 15 flight, Mrs. Darling traveled to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to witness the launch. "I was never so excited in my life as when that thing went up," she said. "Everybody had tears running down their faces."

Mrs. Darling will meet her daughter in Florida for the launch, then accompany her to Houston and to the landing in California.

Also planning to witness the launch first-hand are cousins Marilyn and Charles Darling of Elkhart

"We know that Joe has worked so hard and wanted this for so long," said Marilyn Darling. "We're just very pleased that he's finally going to see his dream come true."

Her husband added that, "I've always been a believer in the space program. Of course, if anybody had skepticism about it, all they'd have to do is talk to one of those astronauts. They'd make a believer out of you."

Of late, however, there's been little time in Allen's life for proselytizing.

"We spend about four hours per day in a simulator, practicing very specific aspects of the mission over and over," he said. "The rest of the day we spend in meetings where the procedures and mission rules are worked out."

He's also had to spend time underwater practicing for the spacewalk he is scheduled to take.

Mrs. Darling says the schedule and suspense are tough on her daughter. "She says she never sees him lately. But she's learned to live with it, and she knows that's what he wants to do," she said. "I think she's a little nervous, but she isn't saying so."

Mrs. Darling saw first-hand this summer what demands are made on Allen. He had slipped away from Houston for a week's vacation at his parents' cottage at Lake Shafer, near Monticello. "He looked very tired when he was here," Mrs. Darling said.

"There might be some rough times, and some things that don't turn out quite right," Allen said when interviewed. "But I don't know of any pioneering area where that turned out not to be the case. This project of making space more accessible is a very tough one, but there are a lot of personal rewards.

"There's a lot of fun involved."

There are several firsts associated with the upcoming fifth flight of the space shuttle Columbia.

But one of those firsts holds center stage. For the first time on a manned flight, the major goal is to make the paying customers happy. That will happen if Crawfordsville native Joe Allen and his fellow crew members on Columbia safely deliver a pair of outwardly similar communications satellites to orbit.

The satellites are SBS-C, owned by Satellite Business Systems of Virginia, and ANIK-C, owned by Telesat Canada. Their presence in the shuttle's cargo bay, as well as the makeup of the crew, symbolize the new era of space exploitation.

"The primary purpose of the mission is the two satellites," Allen told The Truth in an interview. "In fact, that's really the total purpose. However, as long as we're there, we will have time to do some other things."

Allen is the son-in-law of Mildred V. Darling of Elkhart.

The four-man crew, largest ever for an American space flight, includes Commander Vance Brand, an Apollo-Soyuz veteran, and rookie pilot Robert Overmyer.

"Their responsibility is primarily to get the orbiter up there safely, get it home safely, and make sure it continues to operate safely in orbit," said Allen.

Allen and fellow mission specialist William Lenoir complete the crew. Both are space rookies, though both have been with NASA since 1967,

"Our responsibility is with the payloads," Allen said. Each of the satellites, manufactured by Hughes Aircraft, weighs more than 7,000 pounds and takes up one-seventh of the shuttle bay. In addition to solar cells, antennae and transponders, each satellite has two small solid-fuel rocket engines to carry it from the shuttle's low earth orbit to the 22,300-mile high orbit where it will operate.

The launch sequence begins with the opening of a clamshell-like sunshield. Next, the coffee-can shaped satellite begins to rotate at 50 RPM, thanks to the large record-player-like spin table on which it is mounted. The spin stabilizes the satellites.

Though the STS-5 mission patch shows the satellites rocketing out of the payload bay, the spinning satellites will actually be ejected at a modest 3 feet per second by explosive bolts.

"Our job really is to assure that they're pointing in the right direction, which means of course that we just point the orbiter," explained Allen. "Then we must release them at exactly the right time, hopefully with an accuracy of about a second. The reason for that is that our releasing of them actually starts a countdown for their rockets."

For SBS-C, which will be the first satellite launched, that automated countdown lasts 45 minutes. During that time, Columbia will use its maneuvering jets to move some 20 miles away. Should some fault develop or be discovered in the satellite at this point, there is nothing the crew of Columbia can do about it.

"It'd be like picking up a firecracker that's burning," said Allen.

When the automatic countdown reaches zero, the satellite's solid-fuel rockets will fire. There will be no photographs or even eye-witness accounts of that moment, according to Allen.

"We're going to turn our windows from it," he said. "Nothing would break, but the windows might be slightly corroded from watching a number of those things light off. NASA just doesn't want to back off from that conservative position, as much as we'd like to look at it." And the camera-equipped, crane-like CANADARM, carried on two of the test flights, will not be aboard to provide a second-hand view.

For Allen and Lenoir, that disappointment may well be mitigated by the chance to carry out the first spacewalks in the new shuttle-era spacesuits. Where the Apollo moonsuits were custom-made, shuttle suits are "off-the-rack." They are composed of a helmet, hard upper torso, lower torso, and gloves. All but the helmet come in assorted sizes. When an inner cooling garment and a life-support module are added, the spacesuit weighs more than 240 pounds.

"Bill and I are spending a lot of time training for that spacewalk right now, in the water tank," said Allen. The plan calls for them to spend three and half hours testing tools in the payload bay, including winches that can close the payload bay doors if the drive motors fail. They will use handrails and foot restraints to maneuver, while a safety tether will keep them from launching themselves as satellites. Said Allen, "The purpose of it is to demonstrate that the orbiter can support an EVA (Extra-Vehicular Activity)."

So the five-day flight of STS-5 will be notable as the first operational, commercial mission of the shuttle; for the first use of an airlock on an American spaceflight; for the largest crew to date in a single vehicle; and for the use of shuttle spacesuits and spacewalk TV. Barring a Soviet Soyuz launch between now and Nov. 11, STS-5 will be the first flight of the Space Age's second 25 years.

For the most part, though. Joe Allen is oblivious to that dimension of the flight, content to leave such things to historians and newspeople. But there is a personal "first" which can't ever be far from his mind. Allen, Lenoir and Overmyer have spent a combined 46 years as earthbound astronauts. Ten minutes after launch Nov. 11, all three will have shed their rookie status. Allen hinted, tongue in cheek, that the happiest man - or at least the most relieved on board will be Commander Brand.

"I commiserate with Vance," Allen said dryly "He's the only one who's ever had to put up with three rookies. But he's keeping up a strong front on it. He doesn't seem to be weakening."

Update: Dr. Joseph P. Allen left NASA in 1985 after logging 314 hours in space on two Shuttle missions.

![]() Return to

K-Mac's Nonfiction Bibliography.

Return to

K-Mac's Nonfiction Bibliography.

Last Revised: May 21, 2009