(originally published in Michiana, a Sunday supplement of The South Bend Tribune, 15 August 1982)

T-minus-4 days

My first glimpse of America’s spaceport came from a turtle-backed bridge over Florida’s Indian River. To the northeast the distinctive sugar-cube shape of the Vehicle Assembly Building caught my eyes looming over the tropical fl ora. So large did it appear that I thought I was just moments from Kennedy Space Center, and I got on with the serious business of getting excited.

ora. So large did it appear that I thought I was just moments from Kennedy Space Center, and I got on with the serious business of getting excited.

But it wasn’t until after a thirty minute, fifteen-mile drive through the heart of Merritt Island’s forests that I passed within a shadow’s length of the VAB. I parked in the press site lot and spent the next several minutes staring across the street, trying and failing to get a sense of the building’s true size.

Though the VAB stands two-and-a-half times as tall as the Notre Dame library and is as capacious as thirty Century Centers, it persisted in seeming smaller. Such is the scale of endeavor at the space center that the world’s largest scientific structure fits right in.

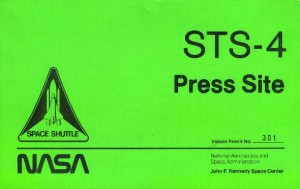

Arriving Wednesday evening for the Sunday, June 27, launch of STS-4, I found the press site nearly deserted. Columbia, poised atop Pad 39A and still encased by a protective gantry, was visible beyond the calm water of the barge basin and three miles of flat brushland. The view through my longest camera lens–205mm–promised better launch photographs than I’d planned on.

Arriving Wednesday evening for the Sunday, June 27, launch of STS-4, I found the press site nearly deserted. Columbia, poised atop Pad 39A and still encased by a protective gantry, was visible beyond the calm water of the barge basin and three miles of flat brushland. The view through my longest camera lens–205mm–promised better launch photographs than I’d planned on.

The press grandstand was empty, the color television monitors hanging from its columns still encased in plastic. The networks’ broadcast booths were still, as were the dozen or more trailers housing the wire services, Voice of America, and other news agencies. The giant countdown clock was dark.

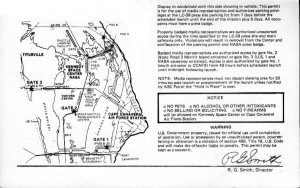

Only in the press center was there light and life, and even there most of the humanity afoot wore NASA, not press, IDs. The small domed building houses NASA’s public affairs staff and provides desk space and pay phones for itinerant newsfolk like me. I signed up for several tours, picked out seats in the center and the grandstand, and registered with the photo office–completing my three-item list of crucial first-day tasks. Literature racks filled one curving wall, and before I left for the night I collected one copy of each item–a six-inch stack.

By 8 the next morning, there were two rows of cars in the press lot, and a few longtime space correspondents such as Howard Benedict of AP and John Noble Wilford of the New York Times were in evidence. A handful of tripods weighted with water-filled jugs marked coveted vantage points along the water’s edge and the hill crest in front of the grandstand. Notes–some stern, some imploring–were taped to the tripods to ward off poachers. But the CBS technicians were sunning themselves behind their booth, and the sparsely attended morning briefing lasted but seven minutes. The crush had not yet begun.

To get your bearings in the 140,000 acre space center and the adjacent, pad-dotted Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, you need two things: a map and a tour. Each year, hundreds of thousands of tourists take the extensive bus tours offered by the Visitor Center. The morning press orientation tour I went on was very similar to those, except we had a NASA PAO for our guide, a more flexible schedule, and access to some usually restricted areas.

To get your bearings in the 140,000 acre space center and the adjacent, pad-dotted Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, you need two things: a map and a tour. Each year, hundreds of thousands of tourists take the extensive bus tours offered by the Visitor Center. The morning press orientation tour I went on was very similar to those, except we had a NASA PAO for our guide, a more flexible schedule, and access to some usually restricted areas.

I hadn’t realized that most of the historic launch sites were located on Air Force land. In retrospect, I should have. Our early launch vehicles–Redstone, Atlas, Titan–were converted military missiles. It wasn’t until the arrival of the Saturn family of rockets in the mid-1960s that NASA had launch vehicles–and therefore needed launch facilities–wholly their own. That was the genesis of Launch Complex 39.

The heart of Complex 39 is the 525-foot-tall VAB, and, like Rome, all roads seem to lead to it. Here the Apollo program’s towering Saturn V moon rockets were assembled and checked out. Now shuttle orbiters are here mated to their external tanks and boosters, atop the launch platform which a tracked crawler carries to the pad. Attached to the VAB is the four-story launch control center. Two of its four firing rooms have been reconfigured for the shuttle era.

The heart of Complex 39 is the 525-foot-tall VAB, and, like Rome, all roads seem to lead to it. Here the Apollo program’s towering Saturn V moon rockets were assembled and checked out. Now shuttle orbiters are here mated to their external tanks and boosters, atop the launch platform which a tracked crawler carries to the pad. Attached to the VAB is the four-story launch control center. Two of its four firing rooms have been reconfigured for the shuttle era.

Nearby and dwarfed by the VAB is a brown and silver structure with two hangerlike bays. Though both were empty during our tour, now both are occupied for the first time. Challenger is in Bay 2 being outfitted with engines for its first flight next January, while in Bay 1 Columbia is being outfitted for its first operational flight this fall. (One of three rookie astronauts on STS-5 will be Joseph P. Allen of Crawfordsville, Ind.)

Two miles away via towway is the enormous runway where the shuttle orbiters land–at present on the back of a 747, but before long, direct from orbit. The seemingly smooth three-mile-long runway is in fact scarred by 8000 miles of quarter-inch-deep grooves, which help water drain off and protect against skidding.

A turnpike-like crawlerway of tan Alabama river rock begins at the doors of the VAB and stretches more than three miles east to Pad 39A, from which most Apollo and all shuttle missions to date were launched. A dogleg north and another mile brings you to Pad 39B, where we stopped and disembarked for a closer look.

Pad 39B was and will be again a twin to 39A. Inside the security fence and octagonal perimeter road are fuel tanks, a water tower, and the concrete hardstand of the pad itself. The hardstand is 50 feet high and split by a firebrick-lined flame trench. Though only five Apollo-era missions started from Pad B, the firebrick is deeply scorched. Viewing it, I am suddenly content to watch the STS-5 launch from the safe remove of the press bleachers.

Nearby, a painter was sitting astride one of two seven-foot-diameter pipes, demarking a black band around it. During launch, 300,000 gallons of water rush from the water tower through the pipes to the hardstand in just 20 seconds. The water creates an acoustic barrier which prevents the roar of the shuttles own engines from reflecting off the hardstand and destroying it.

Nearby, a painter was sitting astride one of two seven-foot-diameter pipes, demarking a black band around it. During launch, 300,000 gallons of water rush from the water tower through the pipes to the hardstand in just 20 seconds. The water creates an acoustic barrier which prevents the roar of the shuttles own engines from reflecting off the hardstand and destroying it.

Atop the hardstand, a chopped-down verstion of the Apollo umbilical tower and a new Rotating Service Structure are in place. But there was also a work-in-progress untidiness, an incompleteness, which underlined that the pad would not be used until 1985. Until then, the action would be at Pad A, centerpiece of our panoramic southerly view.

The rest of the tour flew by, and only a few moments stood out. The “NASA Navy”—two white and blue recovery ships, docked behind the solid booster processing hangar. A Gemini spacecraft in the Cape Canaveral Museum—how could two men have spent 14 days in that flying closet? And signs—some cryptic, some telling, some unintentionally humorous:

DO NOT CROSS—DRAINAGE DITCH INFESTED WITH POISONOUS SNAKES

CARS WITH CATALYTIC CONVERTERS NOT PERMITTED INSIDE

NO LONE ZONE

WARNING: DURING LAUNCHES FROM COMPLEX 36,

THIS IS A CONTROLLED AREA. PARK AT YOUR OWN RISK

When we returned to the press site, we found it bustling at last—the lot filling, Tripod City growing, cables underfoot multiplying. A feisty full house showed up in the briefing room to hear, in response to questions about the classified military cargo, the first chorus of the “Air Force/NASA No Comment Blues.”

Afterward, many hunched over minicomputers and portable typewriters, or rushed, notes in hand, to the phones. There was a tangible energy in the air, and it would grow more intense as launch tinme neared, buoying us up and binding us together into one camera-clicking, question-asking organism.

That boost came in handy, replacing what a broiling July sun and oppressive humidity were draining away. Body-drenching sweat ended only when the body-drenching thunderstorms moved in each afternoon. A meal amounted to bad food—usually supplied by the rolling snack bar dubbed the Roach Coach–eaten in a hurry. The schedule of events seemed designed for the big corporate tag teams; solo acts faced marathon days and short nights. At times coffee, soft drinks, and anticipation were all that kept us going.

The greater part of Kennedy Space Center is in a pristine state, serving only to keep the major facilities safely spaced from each other. As a consequence, one area is set aside as the Canaveral National Seashore, and the rest as a wildlife refuge. But since I couldn’t work in a wildlife tour, I saw little of the fauna.

At the press site, we were blessed with fire ants and giant wasps. A three-inch golden spider hung in its web from a speaker by the press center doors—there day after day, it was adopted as an unofficial mascot. Overhead, a crane, vulture, or bald eagle appeared from time to time. Driving in, I twice encountered vultures feeding on the crushed remains of turtles by the side of the road, and once spotted a wild boar at the edge of the brush. But of crocodile and panther, bear and manatee, I saw nothing.

But the 1500 media people made up a colorful zoo which more than compensated for the shyness of the local wildlife. Of the three main species, the career professionals were the least numerous and most drab. These were the men and women on expense accounts, staying at the best and closest motels. They were the ones who had learned to hang all their ID badges from a neck chain, and were called on by name by the briefing moderators. By TV, radio, and newsprint, they kept the country informed as the countdown progressed.

The fringe media—the free-lancers, the feature writers, the specialty magazines, the college newspapers—were a more happy and relaxed species. It was obvious that many of them, like me, were children of the Space Age, and just tickled to be there.

The photographers are the geeks of the media, burdened by heavy bags of gear and the nagging fear that something would go wrong and they wouldn’t get the shot.

The hurry-up-and-wait quality of the scheduling often threw groups of strangers and bare acquaintances together for long perios of inactivity—sitting on idling buses, or standing by our tripods waiting for the next photo opportunity. During such times there was a good-natured camaraderie that gave time wings.

Astronauts were in surprisingly short supply. Though a few unconfirmed sightings were reported, the media mob’s first real chance to cross paths with anyone in blue was Friday, when the STS-4 crew of Ken Mattingly and Hank Hartsfield was to fly in from Houston in twin T-38 jet trainers. Consequently, there was a good turnout for the arrival ceremonies at Patrick Air Force Base, 20 miles south of KSC. According to the plan, the astronauts would fly over in formation, land, and taxi to the apron where a microphone had been set up.

That, at least, was the plan. But the time of arrival kept slipping, to mid-afternoon, then late afternoon. I amused myself photographing the comings and goings of flea-like OV-10s and lumbering phantom fighters, the waiting limousine, and the Air Force guards with their M-16 rifles. Meanwhile, a nasty storm front was shaping up to the southwest, dividing the sky between blue and black. A race was underway, between the astronauts and the daily afternoon thunderstorm.

That, at least, was the plan. But the time of arrival kept slipping, to mid-afternoon, then late afternoon. I amused myself photographing the comings and goings of flea-like OV-10s and lumbering phantom fighters, the waiting limousine, and the Air Force guards with their M-16 rifles. Meanwhile, a nasty storm front was shaping up to the southwest, dividing the sky between blue and black. A race was underway, between the astronauts and the daily afternoon thunderstorm.

The storm won, driving us inside a hangar. We held out hope that since the storm was headed up the coast toward the space center, there would shortly be no reason to choose its runway over the one where we waited. In fact, after a brief flurry of rain and a few salvos of lightning, the skies over Patrick began clearing again. We took encouragement from the sight of airmen clearing a corner of the hangar and setting up a microphone.

But the storm front passed, and no graceful T-38s appeared. Finally, the astronauts’ wives climbed into the limo, while the NASA TV crew began to dismantle their gear. Three hours after we first arrived, the official word was passed: the astronauts were already on the ground at Kennedy. Grumbling, we trooped back onto the bus. It was little comfort that the official NASA photographer was among those of us caught at the wrong site.

If Friday was a disappointment, Saturday was a disaster.

With the closest media site three and a half miles away from the pad, haze and heat waves often create problems that long camera lenses can’t solve. Consequently, the more ambitious photographers take advantage of an opportunity to place automatic, sound-triggered remote cameras in three areas of swampy land surrounding the pad.

So while many of us were at the Pad 39A periphery Saturday morning waiting for the rollback of the service structure still enclosing the orbiter, the hard-core camera jockeys were donning waders and mosquito repellant and assembling their rigs—some of which featured Plexiglas housings and computer timers. By 1 in the afternoon, hundreds of remotes were in place.

But when I returned to the press site shortly before 6 p.m. for the sunset/nighttime photo opportunity, there were puddles everywhere and many long faces among those waiting for the buses. It didn’t take long to hear the horror stories . A short, brutal storm had toppled or drowned dozens of remote cameras. The photographer from the Miami Herald found his rig lying thirty feet from where he had set it up. Others found their lenses full of water. The Nikon Professional Team had 22 cameras with motor drives put out of action, despite protective enclosures. Worst of all, there were rumors that the Columbia’s delicate tiles had been hit by hail.

The possibility that the launch would be delayed hung over us as we photographed the shuttle against the background of the evening sky. A work scaffold stood against the tail of Columbia, and while we were out at the pad the rotating service structure was rolled back in to aid in the inspection for hail damage.

The sunset was murky and disappointing, and the presence of pad workers kept the brilliant Xenon floodlights darkened. Those photographers who could not afford to stay at the Cape anguished over a postponement, while those with sodden cameras doubtless hoped for a day or two in which to repair and reposition them.

A press release issued at 9 p.m. ended the speculation. The damage was minor. Repairs would be completed during the scheduled hold in progress. Shortly after midnight, the countdown clock started moving again, as fuel began flowing into Columbia’s external tank.

The press site stayed busy all night as well, as a procession of helicopters flew in and out of the fenced-off helipad, and correspondents fought fatigue rather than fight a launch-morning traffic jam. I napped in the back seat of my rental car.

Sunday dawned with me still not knowingly having set eyes on an astronaut. But thanks to those early sign-ups, I was assured of at least a 20-second glimpse of Mattingly and Hartsfield, the middle-aged stars of the show about to begin. The glimpse would come during walkout, a 50-foot stroll from the doorway of the Operations and Checkout building to the red, white and blue van that would take the crew to the pad.

Forty of us waited, cameras at the ready, behind one of NASA’s ubiquitous yellow rope lines in the O&C courtyard. Finally, a confirmed sighting: I spotted Jack Lousma, commander on Columbia’s last flight, walking up from the parking lot. There as a guest, he wore suit and tie, jacket already draped over his arm as a concession to the stifling heat.

Several younger astronauts were there as well, more easily identified because they wore the striking royal blue NASA jumpsuits. Among them were Don Williams of Lafayette, Indiana; the double-doctor husband-and-wife team of Anna and William Fisher; and astrophysicist James van Hoften, who because of his size could never have been an astronaut in the pre-Shuttle days and who reportedly goes by the nickname “Ox.”

Finally Mattingly and Hartsfield appeared on the ramp in their brown Air Force high-altitude suits. Mattingly’s ear-to-ear grin told as well as any interview could how excited he was. B ut Hartsfield, several of us agreed later, looked more somber, as if a bit nervous. If so, it was understandable. Thanks to two cancelled programs, Hartsfield had been waiting 16 years for his first foray into space.

ut Hartsfield, several of us agreed later, looked more somber, as if a bit nervous. If so, it was understandable. Thanks to two cancelled programs, Hartsfield had been waiting 16 years for his first foray into space.

In short order, the crew and astronaut chief John Young boarded the van and were whisked away.

Two hours that seemed like two minutes later, I was in the grandstand with several hundred others, cheering as the clock started counting again after the hold at T-9 minutes. Frenetic activity surrounded me: photographers testing motor drives, radio newscasters narrating the scene, people scurrying down the stands for a last cold drink or up them for a few moments of shade and breeze. A solid wall of bodies stood by the tripods along the edge of the barge basin. The PA system boomed out the progress of the count over the clatter of several dozen typewriters.

Even fully retracted, the rotating service structure partially blocked our view of Columbia on the pad. But we could see the top of the external tank and boosters clearly, and watched the “beanie cap” oxygen vent arm retract with just under three minutes left.

I checked my tripod-mounted camera for a last time, and discovered a switch on my motor drive was in the wrong position. Had I not spotted it, I would only have gotten one picture with the long lens.

Whistles, applause, and cheers went up at T-1 minute, and again at T-30 seconds, spontaneous and joyful. The typewriters fell silent at last.

No chant went up as the clock reached T-10; there was too much to do in those last few seconds. At T-6, a puff of white steam erupted silently at the right side of the pad as the main engines ignited, and a thousand motor-driven cameras whirred to life.

So accustomed to watching launches on television, I had expected to hear the engines’ roar immediately. I was vaguely disappointed until I realized the sound was just delayed, like the sound from distant lightning.

The steam cloud grew, fed by a pale yellow flame at the base of the shuttle, until at T-0 a matching billow of smoke spilled out to the left as the solids came to life. So did the crowd, with squeals of delight and cries of “Go! Go!” nearly drowning out the pronouncement by Hugh Harris that “We have solid motor ignition and liftoff, liftoff of America’s space shuttle on its fourth mission and we have cleared the tower!”

Still in silence and in slow motion, Columbia climbed off the pad atop a yellow-white river of fire five times its own length. Rolling a half-turn to the left, moving ever faster, it began to arch over toward the sea. As it did, the sound finally reached us.

Still in silence and in slow motion, Columbia climbed off the pad atop a yellow-white river of fire five times its own length. Rolling a half-turn to the left, moving ever faster, it began to arch over toward the sea. As it did, the sound finally reached us.

The sharp-eyed saw it before they heard it, as a line of disturbed water racing toward us across the surface of the barge basin. A moment later it enveloped us, a crackling, rumbling bath of energy that made speech and even thought impossible.

Wave after wave rolled over us, the metal roof of the grandstand buzzing as it danced an angry ballet with the shaking ground.

Columbia raced on, slicing through two cloudlets and curving over into the only large area of clear sky. A towering plume of grey-white smoke marked its path. We followed its progress, a thousand heads turning as one, until—30 miles up and well out over the Atlantic—we saw the puff of smoke as the solid rocket boosters separated.

“She’s on her own,” someone behind me cried out in wistful jubilation as the hurtling spaceship was lost to our sight.

I felt for my sun-warmed metal chair and slipped into it, nerves jangling, breath coming in fast, shallow gasps. The space shuttle–that ungainly compromise, by looks kin to ostrich, emu, and other winged but flightless birds—nonetheless flies, the muscles of its rocket motors providing the necessary magic. It is an awesome transformation—from leaden skyscraper to fire-fringed sky-piercer.

I lingered another day at KSC, following the flight on the press room monitors and taking a memorable private tour of Cape Canaveral arranged by the photo editor of Model Rocketry magazine. By the time I finally left for the airport the press site was nearly deserted, the big fish having migrated west to cover the landing, the little fish scattering to home waters.

My jetliner flew home through, over, and around a wall of sunset-lit thunderclouds. The bottom edges of the clouds were aflame, the upper mass a swirling black cauldron, illumed at intervals by lightning within. We bored forward through sight-denying cloud banks and emerged into high altitude snow flurries.

It was a striking architecture—pillars of clouds and interlaced haze, backlit by a warm yellow-orange tapestry, the world below seemingly cloaked by fog as the rain fell. Though I watched out my window until all was darkness, I was not moved by the sight. After the launch, I had a new standard for superlatives, and my thoughts were focused on a tiny spaceship which raced overhead twice before the plane reached Chicago, and twice more before the limo brought me home.

2005 Update: Henry W. Hartsfield, Jr. went on to command the STS-41D and STS-61A missions. Since 1986, Hartsfield has served in a series of management posts in the Astronaut Office and the Space Station program. Rear Admiral Thomas K. Mattingly II resigned from NASA shortly after commanding the STS 51-C mission. Space Shuttle Columbia suffered a catastrophic structural failure during reentry of the STS-107 mission, February 1, 2002, killing all seven aboard.

The following rumination on the future was part of my original 1982 article, but was cut for length by the Tribune, and appears here for the first time. (No, the future isn’t what it used to be.)

WHAT LIES AHEAD?

The fourth flight of Columbia is best thought of as the end of a beginning. What lies ahead?

More frequent flights, of course. In the twenty-one years from Alan Shepard in Mercury to Hartsfield and Mattingly in Columbia, there were just thirty-five flights by American astronauts. The next thirty-five flights will take place by February, 1986–just three and a half years from now. How that will change our conception of space travel is impossible to say for certain. I suspect that the main impact will be to underline the truth of Bob Crippen’s statement after STS-1: “We are really in the space business to stay.”

More flights means more opportunities for NASA’s astronauts, a dozen of whom joined the corps between 1966 and 1969 and still have not flown in space thanks to the decade-long post-Apollo drought. With nearly fifty flight assignments open each year by 1984, they should not have to wait much longer.

More orbiters are on the way. In addition to Challenger next year, Discovery will debut in 1984 and Atlantis in 1985. Nor is the fleet likely to hold at four. NASA and the Air Force already foresee the need for a fifth orbiter just to meet the present demand for cargo space. A private business, Space Transportation Company, has offered to pay for the fifth orbiter in exchange for the right to operate it as a one vehicle space trucking concern. Prudential Insurance would be one of the investors.

Meanwhile, more powerful main engines, a lightweight external tank (both debuting with Challenger in January), and booster rockets of graphite filament rather than steel will add at least 22,000 pounds to the shuttle’s payload capacity-a 34% increase. These changes will be of special importance when the Air Force and NASA begin operations at the new shuttle facilities under construction at Vandenberg Air Force Base’s Western Test Range in California. The southerly flight path needed to reach an over-the-poles orbit robs the shuttle of the boost from earth’s eastward rotation.

All this, of course, is to accommodate the paying customers, which in the next two years include Satellite Business Systems, the Telesat Canada, the Republic of Indonesia, and Department of Defense. Except for Getaway Specials, however, pure science payloads will be few and far between. According to Notre Dame professor A. Murty Kanury, that’s the result of a shortage of funds to turn ideas into experiments. “They (NASA) are in a very tough spot,” says Kanury.

Spacelab provides an example. One of the few notable science payloads now scheduled, Spacelab is a reusable flying laboratory. It includes a pressurized, cylindrical module for the scientists and U-shaped pallets for experiments which must be exposed to the space environment. Spacelab is an extremely flexible system, and it opens up opportunities never before available to scientists who are not career astronauts. Over seventy investigations will be carried out on the first seven-day flight in September, 1983.

But without the European Space Agency, a ten-nation consortium, there would be no Spacelab. ESA, seeing perhaps more clearly than American decision-makers the enormous contribution the shuttle can make to basic science, paid for the development of Spacelab and the construction of the first complete flight unit. It then donated the flight unit to NASA, which will haul it to and from orbit as its contribution.

More than a renewed commitment to basic research is needed if the Space Transportation System is to fulfill its full potential. The shuttle–only one part of the STS–has sharp limitations in several areas. It can stay in orbit no longer than 30 days at a time. It can provide only a limited amount of electrical power to run equipment. It cannot carry satellites to the most desirable orbits. And its cargo-carrying ability has both size and weight constraints.

Two additions to the Space Transportation System, both now being studied by NASA and Boeing, would set aside most of those limitations. They are a small permanent space station, called the Space Operations Center, and a space tug, known as the Orbital Transfer Vehicle.

A permanent space station has been described as the “obvious,” “logical,” and “inevitable” next step in the exploitation of space. Certainly the Soviet Union sees it that way. Its Salyut program, aggressively pursued since 1971, is expected to result in a multi-man space station by the end of the 80’s, probably built around the Salyut 7 now in orbit.

Thanks to the technological edge provided by the shuttle, a modular, expandable American space station could also be in place by 1990. Its jobs would include checkout and repair of satellites, long-term studies of earth resources and space-based industrial processes, and assembly of large structures. The space tug would be a basic part of the station’s equipment, used to carry satellites to and from the high orbits the shuttle cannot reach.

Many expected President Reagan to give NASA the go-ahead for the Space Operations Center when he greeted the STS-4 astronauts on July 4. If that approval comes soon, STS-124 might go something like this:

Odyssey, the fifth orbiter, lifts off from Kennedy Space Center carrying three satellites, several rolls of beam-building material, a small package of electronic components, and a large module with food and propellant. Odyssey’s winged, reusable liquid fuel boosters land at KSC, while the external tank is carried on into orbit, where it joins several others at a growing space tank farm. The orbiter docks with Space Operations Center One, 250 miles up, and discharges its cargo.

Over the next few weeks, space tugs will deliver the satellites to synchronous orbit; astronauts will complete the skeleton of an giant antenna array; Japanese technicians will repair the controller that monitors their small crystal-growing factory; and the food and fuel will keep the 12-person SOC crew hale and their home on station. Odyssey returns home with the depleted supply module, shipments of medicines and crystals, and an old satellite that is to be overhauled and updated. No network TV cameras record its landing. No newspapers carry pictures of its crew, though a few note their safe return in a few lines on an inside page.

That will not mean the flight was unimportant—only unremarkable. Not many people still sit by the tracks to watch trains rumble by, or go out to the airport to watch planes take off and land. But what those enterprises have lost in glamour and romance they have more than made up for through their day-to-day contribution to our communal welfare. So, too, will it be with space travel, but on a larger scale.

For the significance of the space shuttle to Michiana does not lie in new jobs, though a few of our sons and daughters will doubtless journey to space for their livelihood. Nor does it lie in aerospace contracts, though our workers’ skills will continue to contribute to this technical emprise.

The significance lies instead in the enlargement and extension of the hundreds of ways space travel has already changed our lives for the better–most of which go unrecognized. We see the satellite receiving dishes at WNDU-TV, WNIT-TV, and Indiana Cablevision, yet fail to realize how much of our information and entertainment are relayed to us from space. We amuse ourselves with electronic space wars and never connect the technology with spacecraft orbiting overhead. We note the progress of a developing hurricane and forget that without our orbiting eyes unprotected coasts would remain ignorant of the approaching maelstrom. We project worldwide shortages of energy and minerals and ignore resources brought within reach by our voyages in the new ocean of space.

And we take all too casually the ways space flight has changed, not our lives, but our selves. From a jetliner six miles up, the world is still flat. A disc, to be sure, fuzzy at the edges and turned into a patchwork quilt by our farms and cities, but quite capable of being balanced on the back of a turtle. But from 100 miles up, the view is profoundly different. The order we impose on the landscape disappears. The edges of the disc fall away in a graceful curve. The “world” of 15th century Europe has become the planet of 21st century man.

We will never be the same again.