The new arrival at the choultrie on the Rajkot road wore the heavy Kathiawar turban, a man’s turban, but his face was that of a boy. His long dark coat was dusted with the miles behind him, his countenance darkened by the miles ahead.

There were other travelers at the wayside grove west of Lathi–two merchants and their families around a cook fire, a sepoy messenger and his horse, an old man sitting cross-legged before the shrine, a Brahmin and his servant with a camel-cart.

But the youth did not acknowledge them. Avoiding their eyes and pretending deafness at a called greeting, he hung back until there was no one by the well. Only then did he move forward to wash the salt and sweat-streaks from his face, and drink deeply of the cool, metallic water.

After a brief, private obeisance at the shrine, he found himself a place safely away from the others, in the shade of a lime tree. Overhead, green parakeets chattered and small monkeys screeched, but they did not expect Mohandas Gandhi to answer them, and so he could tolerate their presence.

He watched the monkeys cavort for a time, then stretched his slender, narrow-shouldered frame full-length on the ground, hugged his small pack to his chest, and closed his eyes. His body ached with fatigue, but he could not sleep. Hunger made his stomach cry out, and misery gnawed at his heart.

“Look, you, there, a scorpion,” a voice said sharply, close by. Mohandas sat up with a start, then flinched when he found the old man standing over him, a heavy walking stick in his hand.

As Mohandas flinched, the old man stabbed at the ground beyond Mohandas’s feet with his walking stick and flicked something into the air and out into the grass a dozen paces away. “There, the creature has moved on,” the old man said with a yellow-toothed grin.

“Thank you,” said Mohandas with an effort, still puzzled. He did not think he had been dozing, but he had not heard the man’s approach.

“Scorpions are everywhere this season,” he said. The man’s warning had been in Hindi, but now he spoke in Gujarati. “The merchant’s son was stung while playing here, not an hour ago. I saw you come this way and came to warn you. My name is Jafir.”

“Mohandas Gandhi,” said the youth, offering Namaskar, the Indian salute with folded hands. “I am in your debt.”

Without invitation, Jafir settled cross-legged on the ground beside Mohandas. “I cannot remember when they have been this plentiful,” he went on.

Have I been rescued from the scorpion by a leech? Mohandas wondered anxiously. “Perhaps I should find another place to rest.”

The old man ignored the polite cue. “Gandhi–was it a kinsman of yours, then, who was dewan of Rajkot?”

Mohandas swallowed. “My father, Karamchand. Yes, of Porbandar and then Rajkot, until his death.”

“A fine man, I have heard. You are the head of the household now, then.”

Shaking his head, Mohandas said, “No–my eldest brother, Laxmidas, has that duty.”

“Still better, since no son ever took his father’s place without bringing a family strife. Better that you should marry and be master of your own house. Are you married?”

Mohandas nodded, his face brightening. “My wife Kasturbhai bore me a son while I was at school in Bhavnagar. His name is Harilal. I have not yet seen him.”

Stroking the coarse hairs of his flowing white moustache with his fingertips, Jafir said, “A son–you are blessed. Did you say Bhavnagar? You are at the new college, then?”

“Yes,” Mohandas said, squirming.

“You are fortunate. I have heard that the teachers at Samaldas are excellent. It is a splendid opportunity for a young man.”

In an instant, Mohandas’s misery spilled out to paint his face. He jumped to his feet and turned away to hide his distress, but it was too late. “I must find a place where I can rest,” he said curtly, and hastened away.

Jafir made no move to follow. “Sleep deeply, young Mohandas,” he called gently after him. “Sleep well.”

#

Sleep being a refuge, Mohandas slept deeply, and late into the next morning. By the time he arose, the merchants, the sepoy, and the Brahmin were all gone from the choultrie.

But the old man was waiting–clearly waiting, sitting by the side of the road with his walking stick laid across his knees. Mohandas’s shoulders drooped with resignation when he saw him.

“The road is longer when walked alone,” Jafir said, rising to his feet as the young man approached. “You do not mind if I speed my journey with your company, do you?”

“Not if you can keep my pace,” said Mohandas, thinking quickly. “I am eager to see my son.”

“As I can well understand,” said Jafir with a smile. “Let us see how I manage.”

Mohandas thought he could quickly leave the old man behind, wobble-legged and gasping, and regain the solitude he preferred. But it proved a vain hope, as Jafir matched–without sign of distress–any pace that Mohandas himself could sustain. Nor did a brisk stride silence him with breathlessness.

And eventually, his rambling conversation wandered back to the subject to which Mohandas had shown such an allergy the night before. “I was a teacher, when I was younger,” Jafir was saying. “Did I tell you that? I had many devoted students–yes, and a few disappointments. They are all gone now, though, good and bad alike. All gone. What did you say was your interest?”

“The bachelor of arts,” Mohandas said uncomfortably. “I went to Samaldas to study for the bachelor of arts.”

“Ah, very prudent. A B.A. will certainly assure you of a sixty-rupee post in the government service. There is much security in the minor posts. Here, you did not eat this morning–share my rice.”

After a moment’s hesitation, Mohandas stopped and accepted the old man’s generosity. He said nothing, but when he turned and resumed walking, it was at his normal pace. Jafir said nothing as he fell in on Mohandas’s right. They went on in silence together as Mohandas ate, an old man and a young man walking a dusty road as strangers and companions.

“The truth burns my heart every time I refuse to speak it,” Mohandas said at last, with bitterness. “You have been kind to me, Jafir, and I will not lie to you out of pride. Your innocent curiosity stabs into my wounds. The truth is that I am not eager to reach Rajkot.”

Jafir pursed his lips. “I thought there was a weight on your shoulders when I first saw you. I thought to myself, ‘Those frowns will give his face lines like old Jafir’s if he is not careful.'”

Despite himself, Mohandas smiled.

“Do you carry bad news, or fear it?” Jafir asked, peering back over his shoulder at the road behind them.

“It comes with me and through me,” Mohandas said. “I have humiliated myself and shamed my family.”

“How is that so?”

“Because the truth is I have left school, and I will not return.”

“It was not to your liking? Did you squander your scholarship on pleasures?”

“No, no–I was careful with my money, despite the temptations of Bhavnagar.” He hesitated, then plunged on. “I have completely failed to give a good account of myself. The son of Karamchand, and no better scores than 18 of 100 in history, 13 of 100 in Euclid? I am the laughingstock of Samaldas.”

“You seem a bright enough young man. How can this be?”

Mohandas threw up his hands. “From the first moment of class, I am lost. I cannot understand the professors–everything is taught in English, and much too quickly. Geometry, astronomy, history, even Sanskrit and Persian.”

“Then you are unready, not unfit.”

Mohandas shook his head. “I am incompetent–yes, and unwilling. Tell me, what is the sense of it, for an Indian boy to memorize a hundred lines of Milton? Why should teacher and student alike struggle with a foreign tongue when they could speak to each other as easily as we do, in Gujarati? Why are there no translations? I did not have to learn Bengali to read the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore.”

“That is easily explained,” said Jafir, a sudden sharpness in his voice. “If you speak English you will think English, and take on English manners, and begin to forget that you are Indian. The gun is not a conqueror’s only weapon.”

“Should I tell my family, then, ‘Be proud–I am unconquered. I have escaped the obligation of government service. Rejoice–the English will not buy me for sixty rupees a month.'” His voice was scalded with self-hate. “How am I to provide for my wife and son?”

“There are other ways,” said Jafir, “to feed one’s family than service to the viceroy.”

His words passed Mohandas’ ears unheard. “I cannot bear to think of telling Laxmidas,” he said, near tears. “I would almost rather die than carry this shame home.”

“Does this failure exhaust your every ambition? I pity you, then, for a life so empty.”

“Don’t ridicule me!” Mohandas said with an unexpected flash of anger, his dark eyes flashing warning.

Shrugging, Jafir stabbed the ground with his walking stick, leaving an angled gouge. “Is it ridicule to turn your own words back at you? Young men–why do you so love the dramatic? As though your entire life turned on this moment.” He laughed. “You have no notion how much more life there is ahead of you, or what it turns on. Come, I ask you again–have you no other passions, no secret ambitions? Is sixty rupees a month all you ever hoped for?”

Mohandas hung his head sullenly, saying nothing for another score of strides.

“If I had my wish, I should like to study to become a doctor,” he said finally. “It is what I have wanted since my father took ill, and I watched and listened to the English doctors who tended to him. The knowledge to heal, and the burden to comfort–that is a high and privileged service, it seems to me. Yes, I should like to be a doctor, an English doctor, for they are the most learned of all.”

“Then do.”

“I can’t,” Mohandas said, shaking his head. “It is impossible.”

“Why?” demanded Jafir.

“The Vaisnava forbid the dissection of the dead. My father was devout–in respect to him, Laxmidas would never approve of my choice. And my mother takes her counsel from a Jainist monk, a man who wears a mask lest he inhale an insect and harm it, who will not walk in the dark for fear he may tread on a worm.” Mohandas shook his head again. “No, it is impossible.”

“You surrender yourself to their disapproval?”

“I have no choice. A medical education would cost ten thousand rupees, and no one in the family will help me without their consent.”

“Ten thousand?” said Jafir, again glancing back the way they had come. “That is not so much. I have acquired and spent a hundred times that amount in my lifetime.”

“You? You boast. Or you are even older than you look.”

“It is not how long I have lived–it is how far I have fallen,” Jafir said. “Do not think that we all wear our fortunes on our faces.”

Mohandas kicked a stone angrily, and it skittered ahead of them. “It does not matter, unless you propose to make a gift to me of ten thousand rupees.”

“Alas, I cannot.”

“Then what good is my ambition?” Mohandas demanded. “Good only for imagining, and proclaiming my impotence to strangers. ‘Why, yes, I, too, have a foolish dream–‘”

Jafir clucked disapprovingly. “Look there,” said the old man, pointing into the sky ahead. “My eyes are frail–is that kite or crow on the wing?”

Lifting his gaze, Mohandas squinted against the brightness. As he did, a noose of fabric settled around his throat from behind with a whisper, and a massive blow to the middle of his back knocked him forward and drove him to the ground. The noose snapped tight, choking off his cries.

He clawed at it desperately, struck wildly at the air seeking the hands that held it, fought the weight that pinned him in the dust, but all to no avail. In seconds, only Mohandas’s lungs were still fighting. The rest of his body was bound into a single great spasm of panic and pain, frozen rigid by the screams of knotted muscles. Death was agony. Dying was an eternity.

Then, unexpectedly, the weight on Mohandas’s back vanished. The cloth noose whipped free, burning his throat, and was gone. Between retches and coarse, racking gasps, Mohandas raised himself weakly to forearms and knees, his head touching the ground as though he were praying.

“I have killed the boy who was in such misery,” Jafir said commandingly. “But I have spared the boy who cared enough to fight me. He is free now. Allow him to pursue what he wants.”

With a great effort, Mohandas raised his head and turned toward the voice. He saw Jafir standing a few strides away, calmly knotting his sash around his waist–the yellow sash that moments before he had wielded as a weapon.

“Who are you?” Mohandas asked hoarsely. His throat burned when he spoke. “Madman? Bandit?”

Jafir made a scoffing sound, and drew himself up taller. “I am Thag, a deceiver. I am bhurtote, a strangler. I am Jafir, the last Subahdar in Gujarat. I alone keep the secrets of the noose, the sacrifice of the sugar, and the consecration of the pickax.

“You have failed because your mother’s gods are too soft and weak. Your father’s heroes are cowards. The true power comes from Mother Kali, to those whom she has blessed as her own.

“I could have had your life, and your poor purse, Mohandas Gandhi. But Kali has called me to teach once more. She has sent me to be your ustad, your tutor, in the ways of Thuggee. I will not let you fail. You will learn the way and the art, and they will make you strong. You will have your ten thousand rupees, and more. And the brotherhood of the Black Mother will live on.

“Now get up, and begin your life over.”

Slowly, Mohandas gathered his shaking legs beneath him and rose from the dust. He beheld Jafir with reverent awe.

“Ustad,” he said, tears streaming from his eyes. “Guru. Father. I am ready to learn.”

#

I met Jafir on the bleakest, emptiest day of my life. I was consumed by depression and self-loathing, enslaved by the expectations of my family and the obligations of my new child, defeated by my failure at school. Jafir was strength where I was timidity, certainty where I was insecurity, power where I was impotence, fire where I was as colorless as air.

He was everything that I hungered to be. It was impossible to doubt that his appearance was a portent, that Kali had sent him to claim me. I asked for death, and Jafir showed me its face. I craved direction, and he filled my emptiness with purpose. I was without prospects, and he offered me the wealth that meant freedom. I was drawn to him as I been to Sheikh Mehtab, who taught me guile, at whose prodding I first ate meat, and entered a brothel, and stole from Ba.

But Sheikh Mehtab was a schoolboy, lazy, selfish, careless of his friends, shallow. He deserved neither respect nor the compliant followers he had.

My father had taught me to respect age, and wisdom, and authority, and Jafir embodied all these. He had seen into my heart as through a glass–I could not help but accept him as my teacher.

That his teacher had been bloody Kali did not trouble me, for I was full of anger, and ready to fall into her worship. Nor was I troubled that the cult was banned, the Thug clans crushed by Captain Sleeman when my father was still a boy. There was still power in the very name, and I was certain Jafir knew all of the secrets of those days. I could not refuse the honor he had offered me.

#

To explain his long absences from home, Mohandas told his family that he had taken a job as a messenger for a Bhavnagar merchant. Knowing his fondness for long solitary walks, Laxmidas and his mother accepted the deception, along with the honest promise that he would find a tutor in English and someday return to his studies.

Until then, there was far more to learn than Mohandas had dreamed–the taking of auspices, the omens through which Kali made her will known, bird, wolf, jackal and hare–the secret language Ramasee, the wordless signs and road markings, the signals for murder.

“It troubles me,” said Jafir one day, watching Mohandas clumsily dig a gobba, the round grave, “that I must hasten your initiation. Thuggee is a discipline, and each step a test, from the young scouts to the sextons who dig the graves, to the shumseeas who hold the victim’s hands and feet, the bhurtotes who wield the nooses of Khaddar cloth.

“Nor is that the final initiation, for beyond lies beylha and sotha, hilla and jemadar, subadhar and burka. At any step a man may falter, showing sympathy or fear, or otherwise betraying his unfitness.

“Kali is testing me, to see if I am worthy of being called burka, one thoroughly instructed in the art. The measure of the burka is that, alone, anywhere in India, he can form a gang of Thugs from the rude materials he finds around him.

“Yet to teach you the lore and art, I must go against what I was taught. No Thug kills alone, by Kali’s instruction, and I will not defy her. But that means I cannot bring you into the clan by measures, as I would a young boy, as I was myself. On your first expedition, you must be prepared to join me in Kali’s work. Your first test will be a stern one.”

“I will not falter,” Mohandas vowed.

“You dare not. You were chosen by Kali, and she does not forgive weakness.”

“When will I be ready? Let me prove myself.”

“You will never be ready, no matter how long your test is delayed,” Jafir said. “So it does not matter. But I have made a pact with Kali to give half of the life I have left to your training.” He smiled. “And I am not in a hurry to die.”

So it was another year before Mohandas first tasted goor.

#

The flames of the dung fire flared up, filling the air with the aromatic scents of sandalwood, butter, incense, and herbs. Jafir sat on a carpet before the fire pit, the curved iron blade of his pickax resting on a brass dish at his knees. Mohandas perched silent and motionless on his haunches nearby, watching.

“Once, the world was ruled by the demon Rukt Bij-dana, who devoured men as fast as they were created,” pronounced Jafir. “Kali went forth with her sword to slay the demon, but from every drop of its blood there sprang a new monster. She did not falter, but went on destroying the blood-brood, until they multiplied so quickly that she grew weary, and paused to rest.

“From the sweat brushed from her own arm, she created two men, and gave to one a rumal torn from the hem of her garment, and commanded them to strangle the demons. This they did, returning to her when all had been slain. For her labors and service, she presented them with one of her teeth for a pickax. She bade them pass the rumal and the pickax to their sons, and to destroy all men who were not their kin, for the stranglers alone are her favored children.”

Jafir took the pickax blade and passed it seven times through the fire, once for each blood spot he had marked along its length. Then he turned, placed a shelled coconut on the brass dish and shouted to Mohandas and the empty grove, “Shall I strike?”

Mohandas leapt to his feet and cried his approval.

“All hail mighty Kali, great Mother of us all!” Jafir shouted. He raised the pickax blade over his head and brought it crashing down on the coconut, shattering it to pieces.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi took a step forward, his heart racing, his black eyes glowing with eagerness. “All hail mighty Kali–and prosper the Thugs!”

The auspices being favorable, they traveled five days to the northeast, to the vicinity of Surendranagar. Burying the pickax each night and taking their direction from its point each morning, they made their way along the busy road without attracting undue attention.

On the sixth day, they heard the croak of a mountain crow from high in a tree in a roadside grove, and settled there to wait for the rich traveler that sign promised.

They passed over a potmaker from Ahmadabad, because he was of the Camala caste, which Jafir explained was under Kali’s protection. A trader traveling to a wedding–who was plainly bunij, one worth murdering–was spared because he was in the company of his wife.

“A Thug may not kill a woman, nor leave a witness alive,” Jafir reminded Mohandas. “When my clan numbered fifty, with a dozen stranglers in that number, we thought nothing of falling on a party of as many as ten. But you and I must choose more carefully.”

Finally Jafir settled on a trader in indigo, traveling alone and driving a horse-drawn tonga. The cart was empty, which told Jafir that the trader’s purse should be full.

The trader was talkative and generous, and they made his acquaintance easily. They traveled a whole day in his company, with Jafir riding in the back of the tonga–a courtesy from the trader, on account of Jafir’s age–while Mohandas walked alongside.

They were often alone on the road, and it seemed an excellent opportunity for an ambush, with Jafir perched behind the trader and Mohandas ready to seize the harness and control the horse. But Jafir never gave the sign. For much of the day, Mohandas wondered if he had missed a cautionary omen–the braying of an ass, or a wolf crossing the road from left to right, or the crying of owls to each other.

Finally, Mohandas realized that Jafir was simply savoring the trader’s innocence that these were his last hours, and watching with curiosity to see how he lived them.

It was then that Mohandas understood the liberating power of the inevitable. Kali had chosen their victim and delivered him into their hands, and he would die swiftly when the moment came. But haste was not part of the stranglers’ way, and there was an unexpected pleasure in the waiting.

The thrill of foreknowledge drove out Mohandas’s guilt, until he could laugh as easily as Jafir at the joke the trader had not yet been told, and relish the taste of death to come.

Death came in the night. At Jafir’s whisper, “Bajeed–it is safe,” Mohandas shook the trader to waken him. When the man sat bolt upright in confusion, Mohandas seized his hands, and Jafir whipped the yellow rumal around his throat. It was done soundlessly, and with scarcely a struggle. In the darkness, Mohandas found it dreamlike and unreal, even as they carried the body away to the baras where they would bury it.

Jafir allowed Mohandas the honor of digging the grave in the sand. Then Jafir drew his knife and mangled the corpse in the prescribed manner, spilling the trader’s blood only in the grave itself. When the grave had been filled, Jafir sprinkled flea-wort seeds over the ground, to discourage the curiosity of dogs and jackals.

Of the trader’s possessions, they kept only his horse, which they later sold in Mahesana for 70 rupees, and his heavy purse, which contained more than a hundred silver rupees and a delicate gold ring. The rest they burned, even the tonga, so that there would be no sign that a man had vanished in the night, or that Thuggee had returned to west India.

#

Jafir conducted the ritual of tuponee, the sacrifice of the sugar, in the privacy of a clearing in the jungle well away from any road. When the offering had been buried, Jafir divided the consecrated sugar that remained and presented half to Mohandas, who looked at him in surprise.

“It is true that only those who have strangled with their own hands are thought worthy of the consecrated sugar,” said Jafir. “It is also true that for generations, teachers of the art secretly gave goor to their favored disciples, in the belief that it would speed their advance. So I do now.”

Mohandas’ heart soared with gratitude, and his hands trembled as he held the sacred crystals, waiting.

“Kali, accept our offering, and fulfill your servants’ desires,” Jafir prayed solemnly. Then, sharply, he gave the command to strike. “Bajeed. Ki jai.” He raised his palm to his mouth, and closed his eyes in rapture.

Mohandas found the power of the goor dizzying. His heart raced and his throat burned, until he had to lay back in the grass. The stars shimmered before his eyes.

“Mohandas,” Jafir said, his voice sounding far away, “there were long years when I thought that I would never taste the goor again. This is a gift you have given me.

“It is the goor which changes us, which drives out pity, which gives us our strength. Let any man once taste the goor and he will be a Thug, though he know all the trades and have all the wealth in the world.

“Long years,” he repeated. “You cannot imagine.”

Puzzled, Mohandas asked, “How is this my gift?”

Jafir nodded slowly. “I have kept this from you until now. But it is time for you to know–how it is I am here, and why I was alone.

“I have let you believe that I escaped the great hunt, those black years when the nujeebs of the British demon smashed even the strongest of the clans. Thousands of young Thugs did escape, it is true–I knew many who went into hiding, or joined the armies of the princes of the Indian states, who would protect them.

“But there was no Thug clan, no family, which did not have friends or kin in the jail at Saugor, awaiting trial and execution. No matter what our numbers or where we fled, we were not safe, not even in the Indian states, so long as we lived as Thugs, and did Kali’s work. The Company’s soldiers were relentless.

“Mohandas, my clan never strangled a single white man–no Thug of my acquaintance ever did. But they hunted us to extinction all the same.

“It was not that there were so many of them. The nujeebs were led by Thug informers, the approvers–men who had broken the sacred oath to save their own lives–” His voice trailed off as he stared into the darkness.

“You were arrested,” said Mohandas.

“Yes,” Jafir said with a sorrowful nod. “More than twenty of my clan were captured in the spring of 1832, after a pursuit of hundreds of miles. It was an approver, Noor Khan, who led the nujeebs to our hiding place. Other Thugs who had been known to us denounced us before the judge, and we were sent to a crowded prison to join our brothers waiting to die.

“I was a young bhurtote then. I had seen nine expeditions, strangled no more than a dozen men. But I was facing the British noose as surely as someone like Buhram, who had confessed to nearly a thousand murders.

“No one doubted that all of Thuggee was to be destroyed–there was much talk in jail that this was Kali’s verdict on us. It was known that many women had been strangled, along with holy men, and those of the Camala caste. We had brought this misfortune on ourselves. It could even be believed that it was the approvers who did Kali’s work–

“I was young, and frightened. I did not wish to die, and Thuggee could not save me. I lost the faith. I made a full confession, and offered myself as an approver.

“They tested my truthfulness, and in the end accepted me, commuting my sentence. I served them for the next year. Sixteen Thugs were hanged on my words, and a score more branded and transported for life.

“Mohandas, I am a betrayer.”

Mohandas would not hear it. “No–no, it was the British–“

Jafir shook his head. “No, the blame is mine. But I hate them, Mohandas,” he said in a cold whisper. “I hate them for making me weak. I hate them for the way they have taken what was ours. I hate them for destroying my life and my people.

“I have been a shadow since those days. I spent thirty years in the approvers’ compound at Saugor, until they decided at last that I was harmless. Since then, I have been alone–ostracized, denied the way of my father and his father, denied the blessings of Kali.”

For the first time in long minutes, Jafir looked directly at Mohandas, and his gaze was soft with gratitude. “Tonight, I live again. That is the gift you have given me.”

#

We strangled six other travelers, no two on the same road or the same day, before returning to Rajkot. The profit was divided in the traditional manner, two shares to Jafir as the leader, and one and a half shares to me for my part, less the offering held for Kali’s priests. That division left me with 521 rupees in silver and gold, and jewelry worth an equal amount, or more. I gave fifty rupees to Laxmidas for his support of my household, which greatly pleased and surprised him. The rest I concealed in my house, save for the cost of several measures of fine Khadi cloth, a gift to Kasturbhai.

We made three more expeditions before the rains came. On the last of these, Jafir began my instruction in the making and use of the rumal, and before we returned home, I at last became one of those privileged to murder for Kali. I felt no remorse, only delight. There is a sweetness, unexpected, exhilarating.

The rains meant the end of our first season. Jafir did not stay in Rajkot, choosing to return to Indore. But he returned in October with two horses, and we set off on what would be our longest journey together–a pilgrimage to Kali’s temple at Vindhyachal, on the Ganges. There we offered our thanks, and Kali’s share of our booty from the previous year, in the manner which Jafir prescribed.

Whether the priests knew us for Thugs, we could not say. But the temple had once been such a focus for Thuggee that it was there that Sleeman’s spies and approvers began the terrible campaign against us. To return to Vindhyachal was to reclaim it as ours.

Kali showed her pleasure by favoring us during our return. It is unlucky for a Thug to kill on the way to the temple, but Kali placed seven travelers in our hands on the roads back to Rajkot, and the booty was richer than any we had yet taken.

Jafir had decided that I should know all of the sacred places of the brotherhood, for our next expedition was to the ancient tomb of Nizam Oddeen Ouleea, near Delhi. On the way, he instructed me further in Thuggee lore, and told me tales of Ouleea and other celebrated stranglers. And again, our trip home was most profitable, which only confirmed Jafir in his determination.

So we then set out for Ellora and the temple of Kailasa, carved out of a mountain by Krsna himself, where the strangler’s art is depicted in stone carvings a thousand years old. The journey to that great shrine would take us halfway across India, so Jafir bought a mule to carry back the riches he was certain we would gather.

But on the road west of Dhule, Jafir fell asleep while riding in the midday sun. He slipped from the saddle before I could notice, and fell heavily to the hard-packed ground. Jafir’s horse avoided trampling him, but the mule did not. One hoof grazed Jafir’s temple, and another came down squarely on his ribs–I heard the bones crack.

He died there in the road, cradled in my arms, while the mule grazed nearby, innocent of what it had done.

That was the second time I had watched, helpless, as a man who was everything to me slowly and painfully surrendered his life. It seemed to me that there must be something that could be done, if I only had the knowledge–but I did not have the knowledge. I could not help Jafir, as I could not help my father.

I took it into my heart as a rebuke. I had only learned Kali’s way–life was still a mystery.

I bought sandalwood for Jafir’s cremation, and carried his bones to the sacred river myself. Then I went home to Ba, counted my money, and found a tutor in English. Two months later, I took up my studies to be a doctor–an Indian doctor, from an Indian school.

Kali had freed me by taking Jafir. My days as a Thug were over.

#

“Father, you must come at once!”

Dr. Mohandas Gandhi looked up from the desk in his small examination room to the anxious face of his son Harilal. “What has happened?” he asked, rising from his chair even as he asked. “Is it Ba?”

“There has been shooting in the Jallianwalla Bagh. Bring your bag–hurry!”

They hastened together through the narrow streets of Amritsar toward the garden. Harilal could tell his father little more, for he had only caught the rumor as it rippled outward through the city: there had been a gathering for a Sikh festival in the Bagh, which was often used as a meeting place.

“The man who told me to fetch you lives in a house near the garden. He said that he had heard rifle shots, so many that he could not count, and screaming. The gunfire and the screaming went on for so long that he grew afraid and ran away.”

“What reason could there be for such a thing?” Mohandas asked. “I cannot believe it.”

But as they neared the Bagh, it became clear that something terrible had, indeed, happened. There was a strange wildness in the streets outside the garden–the buzz of angry voices and wailing, the acrid smell of gunpowder hanging in the hot, still late afternoon air.

A woman saw that Gandhi was a doctor and rushed out from a doorway, her face anguished, to seize his elbow and hurry him along. “Come, please help, so many are hurt–”

“What has happened?” Mohandas demanded.

“Soldiers–British soldiers, Gurkhas and Baluchis. They marched in, fired at the crowd until their weapons were empty, and then marched out again.”

“Was there a riot?”

“No! Everything was peaceful.”

“Madness,” Mohandas muttered. “I cannot believe it.” But he allowed her to guide him down one of the narrow entrances to the garden.

Once inside, he found himself on a gentle rise overlooking the vast open courtyard that was the Bagh. At his first clear glimpse of what awaited him, he tore himself free from the woman’s grip and stood rooted by the entrance, struck wordless by what he saw.

The Bagh, spread out below him, was a wasteland, littered with the bodies of a thousand Sikhs, many still, many more writhing in agony. Their moaning assaulted him, overwhelmed him, and he averted his eyes with an abrupt jerk of his head.

Mohandas saw then that empty brass cartridges were everywhere on the ground around his feet. The British soldiers had stood where he was standing, calmly firing down into the hollow while the garden blossomed with blood flowers–

The realization sent a poisoned chill through his body, and his legs weakened.

“Come!” the woman said, grabbing his arm again, almost angry in her impatience with him. “Do something!”

The agony of the wounded was palpable even from the rise. Mohandas could not go down among them, but somehow he did. Numbly, he moved from victim to victim, doing what little he could to staunch bleeding and banish pain, until he could go no farther. It seemed that all of India was dying in his arms, and still he was helpless. He drew himself into a ball on the ground near the speaker’s platform and wept until he could weep no more.

But then, anger began to creep into the hollow left by the exhaustion of his despair, replacing his weakness with the strength of a cold resolution for revenge. Mohandas regained his feet, mounted the platform, and surveyed the carnage about him–slowly, deliberately, unblinking, determined to burn the images into his memory.

He attracted no attention, for he was not an imposing figure–a slender, thick-lipped man in a dusty, bloody suit, with big ears and bristly hair that was rapidly turning white. But the vision he was nurturing in that moment gave him a power that no one who saw him could have guessed. The circle of his life had closed–the massacre of the stranglers and the massacre of the Sikhs were the same act, flowing from the same evil. And he knew what power could destroy that evil.

The wind came up, and it was fragrant with death. “In all your years as a bhurtote, Jafir, you took no prize of value, ever,” Mohandas Gandhi said to the wind. “But before I am done, I will.”

#

Mohandas, jemadar of Thuggee, surveyed the faces of the twenty men in the circle surrounding the fire. They were as different from each other as could be–Sikh and Hindu, Kshatriya and Brahmin, man and boy. But they were one in their purpose, and their belief in the promise.

“Once,” said Mohandas, “the world was ruled by the white demon, Rukt Bij-dana, who devoured men as fast as they were created. Kali went forth with her sword to slay the demon, but from every drop of its blood there sprang a new monster. She did not falter, but went on destroying the blood-children, until they multiplied so quickly that she grew weary, and paused to rest.

“From the sweat brushed from her own arm, she created two men, and gave to one a rumal torn from the hem of her garment, and commanded them to strangle the demons. This they did, returning to her when all had been slain. She bade them pass the rumal to their sons, and to use it to destroy all who were not their kin, for the sons of India alone are her favored children.

“Now the white demon has returned to the land Kali gave to us. The British are the spawn of the devourer, whom Kali sent us to destroy. Because we have forgotten our devotions, and abandoned the worship of the Black Mother, we have become weak, and the demons rule over us.

“It is our task, and our honor, to teach what has been forgotten, and restore what has been neglected, and so make India strong again.”

He took up the pickax and passed it through the fire, then placed the white coconut on the brass plate. “Shall I strike?” he asked.

The gang cried their approval, in a voice that shook the trees of the grove.

“All hail mighty Kali, great Mother of us all!” Mohandas shouted. He raised the pickax over his head and brought it crashing down on the coconut, shattering it to pieces.

They cheered, and answered as Mohandas had taught them: “All hail mighty Kali–and prosper the sons of India!”

Then they sang together, the melody haunting, their voices strong in the dark grove:

Because thou lovest the Burning-ground

I have made a burning ground of my heart–

Naught else is in my heart, O Mother

Day and night blazes the funeral pyre…

#

There are five hundred million of us, and not five hundred thousand of them. We are their servants, their sepoy soldiers, the farmers who grow their indigo and tea. They cannot rule without us.

The brotherhood of Thuggee must grow, until we are everywhere, invisible, until the demons do not know which of us they can trust, and so they can dare trust none of us. They will fear the night, and the light, and the shadows, until fear is all they know.

I do not fear death, because if I die in the service of Kali, I know that she will deliver me to sadhu, ecstasy. The demons will fight us, but they cannot defeat us. Wherever they resist us, we will strike and kill.

The demons will leave this land, or they will die. This I have promised Kali. This, Kali has promised me.

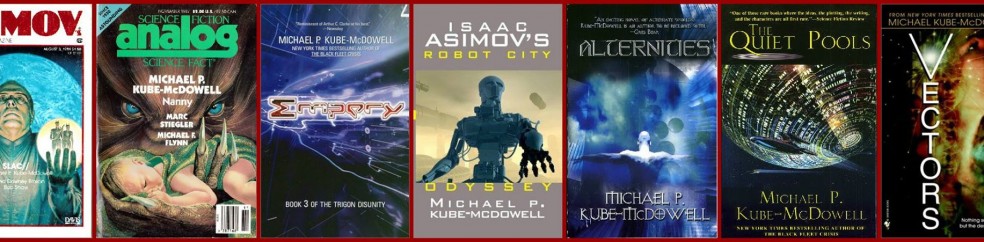

Copyright 1993 by Michael P. Kube-McDowell. Originally published in the anthology ALTERNATE WARRIORS, edited by Mike Resnick and published by Tor Books. Posted to Michael Kube-McDowell’s SFF Net website on March 13, 2005, for the private noncommercial use of visitors to my site. All other rights are reserved by the author. This text may not be offered for sale nor included in a compilation of files offered for sale except by the author or his agent, or with the express permission of same.