originally published in Analog, June 1982

When he returned from lunch to his seventh-floor cubicle in Elgar Industries’ Corporate Affairs building, David Kennerly found the blue message light on his work terminal winking patiently at him. Slipping into his chair, Kennerly called up the message. Since he had left most of his coworkers in the lunchroom debating the merits of various commuter bicycles, Kennerly expected to see the face of Crystal, his contract wife, appear on the screen.

But the message was all text, and not from Crystal. Under the navy-and-rust messagehead of the Educational Coordinator, Elgar Industries, it regretted to inform him that:

We were unable to place your son in Elgar Industries Schools Class of ‘22.

Your son has many fine qualities and we are certain you will be able to find an appropriate position for him. With the growth of the Elgar family, we had this year an unusually large and talented crop of applicants. Our action on Martin’s application should not in any way be considered a negative evaluation of Martin’s potential.

Thank you for you interest in Elgar Industries Schools.

The memo was signed by a D. M. Stein.

Kennerly reread the brief message, as if doing so would change its contents. Then the shock gave way to anger and dismay. I didn’t know they could do this, he thought. I thought they had to take him. I’m a five-year employee. I should be vested in the family ed program.

Guiltily, Kennerly remembered how casually he had taken the application, transmitting it just one day before the deadline. Not even wait-listed! Kennerly felt a sudden rush of shame. Glancing furtively over his shoulder to see if anyone had seen, he purged the message from his screen.

There must be some mistake, he thought angrily. If not, I need a better explanation than this. This Stein can’t brush me off with a memo. This is my son’s future we’re talking about – his career.

Kennerly asked his terminal directory for D. M. Stein’s number and location. We’ ll see about this. He can’t take us so lightly. This is a fringe benefit, not a gift.

The terminal produced the requested information. Good! He’s here – Building Five. Indignation overpowering his other emotions, Kennerly put in the call.

At least Martin won’t give me a hard time, thought Kennerly as he waited for the connection to be completed. Three-year-olds have more pressing concerns…

#

Chapter 4: “… I Owe My Soul to the Company School”

The philosophic model for all the corporate schools which were to follow was the General Motors Institute, of which it has been said that its graduates were in some ways more carefully engineered than the products they went on to make. But without a doubt, the High Priest of the CorpSchool awakening was D. Howard MacIntyre. In the early 1980s, MacIntyre, after much wailing and gnashing of teeth, set up the first school with the express purpose of turning the deficient graduates of government schools into employable human capital. ” It’s a quality-control problem,” said he from his business-magazine pulpit. “Think of it as dropping an unreliable supplier, and you’ll feel better about it.” The faithful listened and obeyed.

-from Griveny’s A Survivor’s Affectionate History of American Education: 1950-2000

(by permission of the author)

#

Deborah Marie Stein’s office was lit more effectively by her 200-watt smile than by the light diffusing through the tinted glass window. But the window carried more information value. It told Kennerly that the Education Coordinator stood more highly in the corporate perquisite hierarchy than he had realized. Even worse, Stein was a woman – an outstandingly attractive woman. The two facts together banished most of his cultivated anger.

“I got – I got a memo from you about my son’s application,” he said, looking everywhere but at her. “I wanted to make sure it was right.”

“I wish I could tell you that it was a mistake,” she said pleasantly. “But I’m afraid that your son was not selected for this year’s class.”

“But I thought it was automatic – five years or more and your kids could go free. I even timed Martin’s birth so that I’d be vested when he was ready.”

“We discontinued that practice last year, I’m afraid. New selection procedures were adopted during the company-wide Overhead Evaluation Program – as I think about it, I’m certain we sent out as all-employee bulletin when it happened.”

Kennerly grimaced. He ordinarily purged the all-corp bulletins without reading them, inasmuch as they were usually news of other people’s promotions and other equally significant minutia. “Is there a wait-list, then?”

“Yes – but it’s short and I’m afraid Martin’s not on it. We get very few withdrawals. There aren’t many long-term employees who decide to leave us.”

He tried to find out from her why Martin had been passed over. But like a county-fair pig, she squirmed away each time he tried to pin her down, leaving him feeling soiled in the effort. Yes, his Education and Employment Prospect Assessment score was above average. No, he had no learning disabilities. No, Kennerly’s job evaluations were not a factor.

“I’m sure you understand that the exact criteria we use must be confidential, ” she cooed. “The primary problem was stated in the memo. There are an unusual number of employees with children in the class of ‘22. The competition was unusually keen. In another year – ‘19, for example – Martin might well have been accepted.”

Kennerly slumped back in his chair, conceding defeat. “Well – can you consider him for the class of ‘23?”

Stein drew back, horrified. “And hold him out of school until he ’s four? That would be terribly unfair to the boy.”

“Why?”

“Why – all his age-mates will be going to school this fall. His friends from the child development center. He’ll feel left out, the stigma of being different. Not to mention the impact on his ultimate achievement! The third year is very important in getting off to a good start.” She leaned forward, elbows on her desk. “And what if he should not be selected next year? Four years old – and still not in school. That’ll be in his records forever, raising questions in people’s minds. He’d almost be sure to end up in the government schools.”

Kennerly bristled. “What’s wrong with that? I went to a government school.”

“So did I. They’ve changed,” she said darkly. “Look – take my advice. Find a family ed counselor who knows his way around and put him to work finding something for Martin. I’ll transmit some names to your work station . It’s really the best way to go. There are nearly two hundred corpschools now. There’s bound to be a spot for Martin in one of them.”

Kennerly looked unhappy, but nodded and rose. “One last thing – I have to ask. I was a little slow getting the application in. Did that -“

“Only in when you heard, not in what you heard,” the woman said reassuringly.

Kennerly smiled wanly. “Thanks.”

As he left the office, he nearly collided with a harried-looking, briefcase-laden man. Kennerly mumbled an apology and continued toward the elevator.

The stranger stopped in Stein’s doorway. “Hey, Dottie.”

She looked up. “Why, if it isn’t Ralph the roving recruiter,” she said cheerily. “How’d you do on the east coast?”

“Super. I signed five of the seven kids I went after – including one UniTech was after – and I stayed within my budget.”

“Fantastic,” said Stein. “That fills the class of ‘22. Come on in. Close that door behind you, and we’ll take a look at what you bagged.”

#

Chapter 7: The Fourth “R” Takes First Place

The NeoChristian schools sprang up like weeds in a junkyard – in church basements, prefab buildings, and the room above the garage, garish mutations of a model that had produced exemplary schools under old-line banners. But in their paranoia the fundamentalists saw a humanist, atheist, or communist behind every semicolon, and to shake off their influence science was rewritten, history reinterpreted. and literature reevaluated. The grand smorgasbord of human thought was reduced by the fundy filter to a watery gruel. But it was the diet the parents wanted for their children, and the students were not heard to complain…

– from Griveny’s Education:1950-2000

#

Kennerly’s home was a second-story apartment an invigorating but not exhausting commuter cycle ride away from the Elgar plant. When he reached it that evening, he made no effort to mask his black mood. He was counting on Crystal to honor their unspoken agreement – that at such times she would neither prod him to talk nor bristle at his inattention, but rather give him time to work it out.

She did not disappoint him. He was allowed to reach the end of dinner with mechanical kisses, monosyllabic statements, and minimal demands from Martin. When the table was clear, he retreated to the screened-in second-story porch and knew that no one would follow.

Settling into a chaise facing the river (a klick down a gently sloping bank from their apartment), Kennerly gave his contract wife a silent stamp of approval. She did not ask him to be anything he wasn’t, and could not have been a better mother had Martin been her own child. He saw her as a far better parent than he could have been – or was now.

Kennerly was well aware that he was uncomfortable with women – though no misogynist, merely the victim of being an only child and of his own shyness. That was the reason he had sought to have a child without the entanglement of an emotional relationship with its biological mother. It was surprisingly easy to arrange; surrogate mother programs were common, though they still accounted for less than 2% of all births. In-vitro sperm sexing had guaranteed that the child would be a boy – Kennerly’s only absolute condition. (For though little girls were at least as appealing as little boys, it was a regrettable fact that they invariably grew up to be women.)

But Kennerly had made one crucial error, one that the clinic’s cursory counseling failed to detect. He was far more attracted to the idea of childrearing than to its reality. But that, too, was solvable. Within a month of Martin’s birth, Kennerly had been advertising for a contract wife.

Crystal had been a find – at 23, eight years younger than himself (and therefore less threatening), pleasant to look at, possessed of modest intelligence but a perceptive wit, at times almost shy. The situation suited her needs; she was a graphic artist of considerable skill but little ambition, and the contract provided security and independence from daily routine without the penalty of solitude. It was a fairly standard sex-optional contract – sixty-day one-party termination, rights and responsibilities clearly spelled out. One unusual feature was that the contract’s term was set not by a date but by an event: Martin’s admission to a residential school.

With that thought, the feeling of being trapped, the resentment toward Martin, came back full force. He recognized the syndrome, calling up the memory from a parenting class. This feeling of responsibility without control was the first step toward parent burnout. Of that the counselor had warned him, and from that Crystal had shielded him – until his tidy plan for Martin’ s future fell apart. And there would be no putting it back together; Elgar was hiring fewer and fewer people they had not trained in their own schools. Kennerly felt a great unfocused hostility – toward Elgar, toward Stein, toward the inventor of E & E assessments for three-year-olds, toward Martin for existing, toward Crystal for what she would think when he told her, and, because there was some left over, toward himself.

A noise to Kennerly’s left made him turn his head. Crystal stood in the doorway in her robe.

“It’s Candice and Tom on the phone,” she said gently. “Are we interested in a party Saturday night?”

“I suppose so. Any special occasion?”

“Their boy was accepted at IBM Elementary. You know Candy and Tom – any excuse to open the bar.”

Kennerly’s face became rigid. “Tell them no,” he said curtly, and turned away. Crystal lingered in the doorway a long moment before leaving. Good girl, he thought. I don’t want to yell at you.

Kennerly lay on the chaise and stared out through the screening at the distorted blobs of light marking traffic on the river. He was only vaguely aware that his teeth were clenched, of the tightness of his grip on the chaise ’s aluminum arm, of the tension in his neck and shoulder muscles. His thoughts were focused on the past. If I’d done the right things, he’d have been accepted, was the general thrust.

Then movement, noise, intrusion – it was Martin, wandering onto the porch with a wooden boat under one arm and a doll and a terry towel clutched in the other. Unceremoniously shedding his burdens onto the floor, he went to the screening and peered out into the night, barely tall enough to see over the sill. Nose pressed into the wire, Martin mad e meaningless wordlike noises of apparent pleasure. Then a moth appeared, startling him and sending him back to the relative safety of his toys. His omnipresent smile did not waver.

Crystal swept onto the porch and gathered up the child and his possessions. “There you are,” she said affectionately. “You know it’s bedtime. Marty.”

“No,” said Martin.

“Yes,” said Crystal firmly. “Say goodnight to Daddy.”

Martin complied, the thumb that had found its way to his mouth garbling the words. Kennerly suddenly realized that, watching Martin, much of the tension had drained out of him. “Come back when you’ve put him to bed, all right? “

“All right,” said Crystal. She seemed pleased.

When she returned, he made room for her on the edge of the chaise. “I saw the Elgar ed coordinator today,” he said. “They don’t want Martin.”

“Ooh. You were counting on that,” weren’t you. How bad was it? Did they say, ‘No, thanks,’ or ‘We recommend you kill it immediately’?”

Kennerly laughed. “Not that bad. I just hate surprises.”

“Misoneist.”

“Yup.”

Their hands found each other, joined. Hers were cool and soft. “There are lots of schools. We could look for a good church school. We could afford it, couldn’t we?”

“No, thank you,” he said coldly.

Crystal pulled back, reclaiming her hands. “I went to one, you know. I don’t think I turned out that badly.”

“No, no,” he hastened to say. “They’re good at some things – like what you’re doing. It’s just that -“

“What that I’m doing? Childrearing? Or art? “

“Well – both. But you can’t get a high-tech job with a church school diploma -“

“Really! Then whom do the Christian Satellite Service and the other twenty Christian businesses in the Fortune 200 hire?”

Her contentiousness spurred Kennerly to lash out. “Well programmed, weren’t you? Look – I can’t stomach their version of reality. I want Martin to know who Shakespeare, Thoreau, and Emerson were. I want him to recognize the rest of the animal world as his relatives. I don’t want him thinking because he’s read one book he has all the answers. All right with you?”

Crystal stood up abruptly. “You want something better for him, you mean,” she said acidly. “Someplace he’ll grow up a little more tolerant.”

“Without the tone you’re putting on it, yes.”

“Fine.” She drew her robe more tightly around her and stalked out.

“Arrgh,” growled Kennerly, closing his eyes against the outside world. He rolled on his side, curled in a quasi-fetal position, and mumbled a few expletives as incantations against intrusion. God, I hope the counselor can straighten this out, he thought, and shortly thereafter fell asleep.

#

Chapter 8: The Odd Marriage of Lucifer and Jehovah, or, Why Does Superman Need Lex Luthor?

It took just a sweep of the legislative wand to transform children from prisoners to consumers of educational services. That same wand brought two new players into the great game of education. It was an old drama – agent vs. publisher, union boss vs. corporate legal hound, reporter vs. celebrity – played out in the new arena of the hospital nursery. “In the Center Crib, ladies and gentlemen, the first bout of the evening, the Family Education Counselor vs. the Corporation Talent Scout” – a relationship at once viciously predatory and incestuously parasitic. One unhappy observer viewed the carnage and opined that, “Those old adversaries God and the Devil are at it again, but you need a scorecard to figure out which is which…”

-from Griveny’s Education: 1950-2000

#

Kennerly looked up from the nameplate on the desk before him – Philip Tanner, F.E.C. -just as Tanner looked up from the records Kennerly had provided him. “Martin had a surrogate mother?” Tanner asked.

“Yes.”

“I don’t see her genotypic profile here.”

“I don’t have one. I never knew who the mother was or anything about her.”

Tanner raised an eyebrow. “Not a do-it-yourself job, eh? Didn’ t you think that was a bit risky?”

“Not all surrogate programs will accept a single father. I had to make some allowances, just as they did.”

Tanner clucked his displeasure. “I suppose that means no work history for the mother, either.”

“That’s right. Is that going to be a problem?”

“Not really. There are plenty of non-corporation schools.”

“What? Just like that, there’s no chance of admission to a corpschool?”

“That’s about the size of it.”

“Why?” Kennerly demanded.

Tanner shrugged. “Not knowing the genetic background or life achievement of the mother is two strikes. Combine that with your own mild underachievement -“

“Now, just a moment!”

“That’s the way I read it,” Tanner said without apology.

“You mean they won’t even look at you without the mother’s records? That’s – discrimination.”

“Yep. And perfectly legal. The private schools were guaranteed absolute freedom in their choice of students, teachers, and curricula. Look – be reasonable. There are fifty applicants for every scholarship position. The company is committing itself to eight years of expense – possibly to sixteen and a job. Why should they bet on a mongrel over a pedigree? Too many people have tried to hide unflattering relatives. If anyone would take a chance on him I’d say it’d be your own employer.”

“If you were right about that, I wouldn’t be here,” Kennerly said quietly. “They gave me your name.”

“Dottie did that?” said Tanner, brightening. “She’s sharp. Really whipped that Elgar program into shape. They were one of the last to start recruiting, you know. Well – we’ll need to look at your family finances. I have to have a handle on what you can afford before I start looking.”

“I’m not sure yet I want you looking, ” said Kennerly. “I just can’t believe that no corpschool would be interested in Martin. He’s got a good E&E -“

“You pay me to know the market, not to massage your ego and wa ste your money on hopeless applications and credentials reviews. And another problem you’ve got – it’s late in the season. A lot of the top schools have already closed their classes.”

Kennerly sighed. “So what are you offering me?”

“I’m not sure yet. The NeoChristian schools are out – a double whammy with the surrogate mother and the contract wife. Unless you’d care to repent and replace the contract with a vow?”

“Thank you, no.”

“Okay. There are about ten independent high-tech programs, doing basically what the corpschools do and competing with them for faculty and students. They keep their admissions open later than most to catch corpschool rejects. We could try them.”

“Same deal as the corpschools? Kennerly was suddenly interested.

Tanner laughed. “Oh. No. You pay them. A lot.”

“Well – what about jobs? What happens after graduation?”

“Catch-as-catch-can, of course. But they do well. Another possibility is that your son will do well enough to attract the attention of the corpschools at the transfer points – fourth, eighth, twelfth grades. There’s a lot of raiding.”

“No. I want better than that for him.”

“I’d be misleading you if I told you you could get it. I can’t even promise you a spot in one of those schools. You might have to content yourself with one of the main-line church schools – Catholic, Lutheran. “

“Give me my records, please,” Kennerly said. Tanner handed over the diskette. “Mr. Tanner, I don’t like your attitude and I can’t buy your conclusions. I’m afraid I’m going to have to go at this another way.”

“Really? You can take that portfolio to any other F.E.C. in town and he’ll tell you the same thing. If he doesn’t, keep one hand on your wallet – he’s a crook.”

“I’m not going to use a counselor.”

“Oh? You’ll do it yourself?”

“Exactly,” Kennerly said, standing. “At least I care more about him than an easy fee.”

“Do you know what admissions officers call applications that come in without an F.E.C. cachet? The scruff pile. If they’re looked at at all, it’s by computer. Very few make it in that way. I can guarantee you won ’t. And you’ll end up spending twice my fee to prove me right – while your kid sits in a public school.”

“You make that sound like a threat.”

“Threaten you? I feel sorry for you. I get a lot of parents like you – unable to face the facts. Your kid learns ten words and two addition facts and you think he’s a genius.” Tanner leaned across the desk. “I’ve got a message for you – it’s okay to be mediocre.”

“You ought to know,” Kennerly said agreeably.

The shot went wide. Tanner merely laughed, shaking his head. “Good day, Mr.Kennerly – much patience and luck to you. You’re going to need both.”

#

Muller’s PROFILES OF NORTH AMERICAN PRIVATE SCHOOLS

12,000 Annotated Entries Including:

-Fees

-Stipends & Scholarships

-Admissions Criteria

-Faculty & Curriculum

-Philosophy

Special Sections on NeoChristian, Corporate, and Fine Arts Schools – Both Day and Residential

+ + + Data Base © 2005 by Muller Publishing. + + +

+ Protected by Data-Scramblertm +

+ + +

Enter name of school or “S” for Selection Sort.

S

Enter subset delimiter or “A” for alphabetical review.

North Central Zone

3921 entries. Enter additional delimiter or B to begin.

Exclude NeoChristian

2218 entries. Enter additional delimiter or B.

PARENTAL GENOTYPIC RECORDS NOT REQUIRED

1314 entries. Enter additional delimiter or B.

SCIENCE/TECHNOLOGY TRACK AVAILABLE

1110 entries. Enter additional delimiter or B.

CLASS OF 2022 OPEN

173 entries. Enter additional delimiter or B.

“Jesus!” Kennerly exclaimed.

SCHOLARSHIP PLUS STIPEND AVAILABLE

No entries. Reset to previous level.

TUITION LESS THAN $3500 YEARLY

9 entries.

COED AND MULTIETHNIC

2 entries.

B

East Lake Academy of Mathematics and Music. Fnded 1987, enrlmnt 116, flltm stff 7, plcmnt 68% (1 yr). Specialty: “fundamental patterns of Universe as expressed in mathematics and classical music” Full report: T-210.

Kenowa Free School. Fnded 1975, enrlmnt 460, flltm stff 18, plcmnt N.A.. Specialty: student-directed exploration, “wholistic” development; no required studies. Full report: K-108.

Six equally unproductive sorts later, Kennerly’s amazement had yielded to outrage. Racism, religious indoctrination, and political chauvinism were trumpeted as “specialties” – not always euphemistically. One school promised that all reading materials were so sex neutral that characters weren’t identified by sex. Another assured parents that “one-worlder propaganda” had been expunged from its social studies courses. An all-girl school offered a program to provide its students with the “proper skills and attitudes” for serving their husbands in accordance with Biblical precepts.” There were Klan schools, atheist schools, Scout schools; schools emphasizing astrology, survival training, and sexual fulfillment; schools where instruction was in Spanish, Esperanto, and even Latin. Left, right, or center, Kennerly was appalled by the narrowness – and in that respect, he was forced to admit, his precious science schools were no better than the NeoChristian schools he despised.

“I won’t be a part of this,” he vowed silently. “I won’t turn Martin over to fanatics of any stripe.”

To his credit, Kennerly did not recant when he realized that he had narrowed the options to one.

#

Chapter 12: “Mom, Meet Miss A-210 Series Five”

SHORT ANSWER: What is patient, efficient, and unprejudiced, treats students as individuals, uses a variety of techniques, and makes only modest financial demands?

The computer-based teaching machine.

ESSAY: Why did it take the educational establishment so long to catch on?

Silly boy – computers have no union.

HISTORICAL – INTERPRETIVE: What happened to the displaced teachers – those lacking the academic strength for curriculum development, the practical experience for business, or the moral qualifications for God (that is, most of them)?

Who really cares? It was all their fault anyway, wasn’t it?

-from Griveny’s Education: 1950-2000

#

Jessica Adams, principal of Hawthorne Elementary, was not a good actress. Though she rattled off her lines flawlessly – “How nice to meet you – always gratified by parents’ interest – very proud of our school – happy to show it to you” -her delivery and demeanor did not convince. What’s more, she rushed her monologue – the one about dedication and concern and growth and achievement. Kennerly thought that a shame; they were such nicely turned words.

Ten minutes after he had appeared at the central office, Adams was abandoning him at the doorway to Classroom 100. She urged him to wander freely and satisfy his curiosity, and extended a lukewarm invitation for him to stop back and see her if he had any questions. Her exit was in character; she walked away as though retreating to secure ground.

The high-ceilinged stupa-like classroom was filled with row upon row of chest-high cubicles. Above each cubicle rose a metal stalk tipped by red and blue lights, one or the other of which was lit in most cases. The partitions themselves were decorated with posters, an assortment of little fuzzy creatures, and a surprising number of what appeared to be award certificates. Stepping closer to a nearby cubicle, Kennerly read the citation on one – NEATEST STUDENT (JULY).

Kennerly stood for a while watching the four adults who were roaming the aisles. The red and blue lights seemed to be for them; presently Kennerly deduced that red meant “I need help” and blue “Yes, I’m working.”

The room was noisy – fans, keypads, nasty laughter, many hushed voices. Kennerly poked his head over one partition and found a girl he judged to be eight or so intent on the screen of her teaching machine. The word “fountain” appeared there in large letters. The child moved her lips silently, then touched a large green key and said out loud, “Fountain.”

“Very good, Ginny,” said the machine in the voice of the video actress whose poster hung from one of the cubicle walls. “Let’s try another.”

“Hi,” said Kennerly. “My name’s David. Can I talk to you for a minute, Ginny?”

“Go away,” the girl said without looking up. “I need ten more points for a music break. Come back after.”

Taken aback, Kennerly moved on down the aisle. He stopped several more times, once to watch a mosquito go through its life cycle in an animated computer-graphics world.

“Do you like science?” Kennerly asked the boy in the cubicle.

“Yeah,” the boy said without enthusiasm. “It’s got better pictures than history.”

Alarmed but wary of generalizing, Kennerly moved to another section of the room and asked more pointed questions: What’s a verb? Who’s the president? Name the ten planets in order. He rarely got right answers, even when he took a question straight from the screen the child had just finished reading. He always got puzzled looks, as though only machines, not people, should ask questions. A half hour later he was back in Adams office.

“Problem, Mr.Kennerly?”

“Yes! I want an explanation of what I saw out there. Those kids are practically chained to their chairs to keep them working. Or bribed. Or flattered for every little success. If there’s one of them that’s excited or happy, you’re hiding ‘im.”

“It’s summer, Mr. Kennerly. They’d rather be outside.”

“I don’t blame them! That place is like a factory.”

“I believe it was modeled after one. Two students to a cubicle – 24 cubicles to a supervisor – four supervisory units under one production manager.”

Kennerly blinked in surprise. “Well, it isn’t at all what I thought it would be.”

“I suppose you’re offended by the teaching machines,” she said. It sounded like the start of another well-worn monologue.

“No!” Kennerly snapped. “It’s not the teaching machines. It’ s the kids. The only life I saw out there was a paper fight over the partitions.”

“We do the best with what we have. Mr. Kennerly,” said Adams, folding her hands on her desk.

“With what you have! You have more gadgets and hardware than AT&T.”

“Hardly. And I was not referring to the equipment in any case,” she said quietly. “I was referring to the students.”

That slowed Kennerly’s charge. “What do you mean?”

“We have about forty-six percent of the school-age population. Which forty-six percent, do you think?”

“Ah -“

“I’ll tell you, Mr. Kennerly. The forty-six percent that no one else wanted. The kids who were produced by accident or out of duty and whose parents haven’t found a use for them since. Most of the handicapped. Most of the easily identified minorities. That’s why you saw what you saw. And you can’t lie to these kids. They know who they are, too. They know that their best chances for success are hustling and dependency. They know they’re not the future leaders of government and business. And if any kid among them decides he’s going to be the exception, he’d better be strong enough to take the others turning on him.

“But it wasn’t like that, you say. What happened? Democracy. Freedom of choice. Tuition tax credits. In approximately that order. Everyone got what they wanted. The corpschool parents got a meritocracy. The private-school parents got cocoons to wrap around their children. These parents got a twelve-month baby-sitting service.”

With the actress banished and the person erumpent, Adams continued in a softer voice. “If you send your son here, we’ll do our best by him. Our programs are excellent – if the child is up to them, if you can keep him caring. But realize he’ll be surrounded by contrary models. I’m sorry – for you and for myself – but that’s the way it is.”

#

Kennerly squinted at the figure seated at the top of the stairs, blocking the path to his apartment. It proved to be Tom of Candice-and-Tom.

“Hi, buddy,” said Tom, rising as Kennerly neared the top of the stairs. “I thought I’d drop by and find out why you’re snubbing our party tomorrow.”

Kennerly sighed, moving past and unlocking the door. “I’m not snubbing you. I ’m just – we had other plans already. It was kind of short notice.”

“That’s not the way I heard it,” said Tom, following Kennerly in and making a beeline for the liquor cabinet. “I heard you were all wound up over Martin being rejected by Elgar.”

“So you had to make sure you had a chance to rub it in, right?” said Kennerly, disappearing behind the bathroom door.

“My, you are bristly, aren’t you. It’s just one rejection.”

“Yeah, well, I thought I had a lock on it,” Kennerly called over the sound of running water.

“No such thing as a sure thing,” said Tom, settling on the couch with his drink.

“Thanks for that wisdom,” said Kennerly, appearing at the doorway, wiping his hands on a towel.

“No charge. So what have you been looking at?”

Kennerly capsulized his last three days.

“Sounds like you’ve about run yourself out of options.”

“I’m not ready to say that. I’ll keep looking. Maybe we’ll have to move. But somewhere there’ve still got to be some schools like the ones I knew.”

“Oh, Dave buddy,” said Tom, swirling the ice cubes in his glass. “Looks like I’m going to have to play Confrontation Therapist, because you don’t seem to hear yourself. You’ re the cause of your problem! I don’t know if you know what you want, but you’ve got so many things you don’t want there isn’t anything in the real world that’ll please you. You’ve got to realize – kids are tough! They can handle imperfection. They can tell sense from nonsense. Be a little bit more realistic, and your problem’s going to disappear.”

“I think I am being realistic,” Kennerly said stiffly.

“Crocko. That wonderful school you’re remembering never existed. Sure, you loved it. But the kid next to you was dying of boredom. The girl behind you got pregnant on the team bus. Your best friend only cared about the sports. The teacher that lit your light chucked it all to sell insurance. You’re in fantasyland, Dave. Wake up.”

“Pretty easy to talk when your son got into IBM. He’s set for life.”

“But does he want to be, that’s the question. How would you feel if your whole life had been planned by your father – before he even knew your interests? The truth on that IBM thing is that Candy got the last word. I wish Chris was going somewhere else, and I don’t think he’ll last there. If he doesn’t start to kick somewhere along the line I’ll disown him. Dave – you don’t owe your son a good job and a happy life. Those are his problems. If you get him walking and talking without making him crazy, you’ve done your part.”

“Is that how you rationalize it?”

“Whoa,” said Tom, holding his hands up, palms out. ” Here’s where I get off. It’s not worth fighting over. I just hate to see you kick yourself for no reason.”

“Right. Have a good party.” It was an invitation to leave; his visitor hesitated, then took it.

Kennerly was still seething forty minutes later when Crystal returned, a sleepy Martin clinging to her neck. “Put him to bed,” Kennerly ordered. “I need to talk to you.”

“Talk to me or castigate me? I’ll stand for one but not the other. I thought that, since you couldn’t or wouldn’t talk to me about it, maybe you could talk to Tom. I was wrong.”

“You had no right to tell him. You should have minded your own business.”

“I thought Martin was my business.”

At that moment, Martin added a cranky wail to the conversation – the reedy cry of a tired three-year-old.

They were frozen that way a moment, a domestic tableau, her gaze defiant, his hard and unyielding. Then, mumbling “I gotta get out of here.” Kennerly leaped to his feet, scooped up his keys, and fled the apartment.

He did not return that night, nor the next. When Monday came with no word from him, she called his office.

“He took five days’ vacation,” the group secretary told her, surprised. “Didn’t you know?”

Crystal assured him that, yes, she knew, she had just gotten confused. And tried not to care about the rumors her call would inspire.

#

It was a week before they saw him again, pulling up in front of the apartment in a rented electricar. He took the steps three at a time, calling out their names. He did not merely admit himself to the apartment, he made an entrance, sweeping Martin up in his arms on sight.

“Hey Marty! Time to go see where you’re going to spend the next few years. All right?”

To Kennerly’s delight, Martin burbled, “School.”

“Crystal -“

“Not interested. I need to tell you -“

“Talk on the way. Come on.”

“Now? Martin needs to be getting to bed.”

“So he’ll sleep in the car.”

“David – I’ve decided to terminate our contract.”

Kennerly was unfazed. “That takes sixty days. In the meantime, grab what you’ll need. You don’t have to come with me, but you do have to come with him. Figure to be away a couple of days. The weekend.”

“Go to school now?” Martin demanded.

Kennerly ruffled the child’s hair affectionately with his free hand. “Soon, Marty. Soon.”

Kennerly drove south, into farm country, with Martin curled up on the small back seat. Kennerly himself seemed cheerfully oblivious to his wife’s pronounced coolness toward him, denying her the chance to express her anger. Presently she lowered the seat back and turned away from him, withdrawing via sleep.

She was roused by the noise and movement accompanying a battery swap. While the mechanics swarmed over the back of the car, she ran a brush through her tousled hair. “We must be going quite a ways. What time is it?”

“Four A.M. We’ll be leaving the highway soon, and I wanted to make sure we had a full charge.”

An attendant appeared at the driver’s window to return Kennerly’s Cashcard.

“Do you want me to drive?” she asked. “You’re not used to this, and I don’t want to end up in a ditch or under a truck.”

“I’m fine. I drove this twice last week alone.”

She looked away, out her window, and said nothing until they were on the road again.

“Aren’t you going to talk about this at all?” she demanded finally. “You take off without a word for a week and bounce back in like you went to the corner store. Where were you? What did you do? What is this place we’re going? At least tell me something about it.”

“I’m not going to talk about last week,” he told her, “b ecause apologies are too easy and don’t mean anything. And I want you to arrive at our destination without any preconceptions. Go to sleep again. We’ll be there in about six hours.”

At twenty after ten the next morning, Kennerly slowed the car and turned off the two-lane country highway and onto a still narrower dirt driveway. As they crested a small hill, Kennerly stopped the car, and the cloud of dust they had kicked up briefly engulfed them.

“My God,” Crystal exclaimed as the dust cleared. “Is this it? It’s a cave, for Christ’s sake!”

Kennerly just laughed. “Not quite. Come on.”

It was, in fact, an earth-sheltered home, buried into the side of a hill except for the long south-facing wall studded with doors and expanses of glass. An awning of solar panels ran the full length of the wall, and behind it grass grew on the roof.

Kennerly produced a key and let them in. They found themselves in a roomy but empty and carpetless chamber. “Living room or den,” Explained Kennerly. Martin was drawn to the cobblestone north wall – a strange and wonderful discovery for a child accustomed to bland plaster walls. The air in the house was pleasantly cool, and surprisingly dry.

“Doesn’t anyone live here?”

“New owners haven’t moved in yet. Come on – while he’s busy.” He nudged her toward a hallway, and led her into a room that opened off it.

“This is where I decided to put it,” he said. “I’ve ordered one of the best smart terminals available – two phone lines, full data-base access, lots of on-site memory, voice capability. Plus the house is already wired for 400 video channels, direct from the satellites. I’ve signed up for a phonics tutorial program from a company called Home Learning, and I’m looking at a super science program from Michigan State. There’s a surprising amount of ed software available. Oh, and books – There’s a plan that will put a hundred books in Martin’s room and replace half of them every three months. Real books – so he can curl up in a hammock out in the fresh air and read.”

“You bought this house.” It was almost an accusation.

“Yes.”

“To quit your job and move here with Martin.”

“No. That’s the beautiful part. I’ll keep my job – and do the same work. From here.”

“Your own little cottage industry.”

“In a way.”

“Are there any neighbors? Kids his own age?”

“There’s two families just a klick away if you cut through the fields. One has five kids, then there’s a younger family with two. A nice healthy mix of ages.”

She shook her head. “I never thought you’d run out and hide from the world.”

“I thought you’d call it that.”

“It is! Instead of trying to fix the things you don’t like about the schools at home, you’re giving up on them.”

“Will you listen to why, or is your mind closed? “

“I’ll listen.”

“Thank you,” he said, relieved. “First – I need to do something now, for Martin – not for his children. I can’t start a campaign that even if successful won’t show any results for five, ten or twenty years. I’d be making him a kind of burnt offering to my idealism.

“Second – think about what it’ll be like for Martin. He won’t be locked inside during the best part of the day. He won’t be a slave to a schedule that ignores his individuality. He’ll have the real world in his back yard and his books. He and I will spend more time together. He’ll grow to see me as a competent person, because he ’ll see work as a basic element in living. He won’t see learning as something that only happens in a certain building on certain days with certain people. Still with me?”

“Still with you, ” said Crystal, a smile playing on her lips.

“Okay. Clincher. This is what’s coming. I’m not the first, and more will follow. Big picture, now. Industrial revolution takes wage-owner out of the family store, off the farm – away from his family. Technology. The knowledge explosion, makes parents feel incompetent to teach their kids themselves – which they managed for most of human history – so they bundle them off to specialists and experts. Parents lose credibility. Family weakened. The crazy years. Looking back, hard to see a way around it. Parents didn’t have the time or the expertise. But those excuses aren’t good any more – not now that microelectronics will let us and our kids come home.”

“You’ve got it all wrapped up in a neat little package, haven’t you?”

He shook his head. “There’s a string dangling. You. Your contract.”

“Oh – you won’t need me now.” She hesitated. “If you agree to the termination, we can avoid sixty days of awkwardness.”

He stepped toward her. “I’ll agree to the termination – on one condition. That we replace the contract with a vow.” She stared at him. “I’m going to need you more than ever – now, and when Martin leaves, however many years from now. And I think I’ve been missing a lot, holding you at arm’s length.”

“I could have told you that,” she said wryly. “I don’t know David. Are you sure you’ re not just trying to complete the happy little picture – momma, daddy, baby, and the little house on the prairie?”

“I’m sure, ” he said, taking her hands. She did not pull away.

“Hmm. I’ll have to think it through.” She pursed her lips. “But you do surprise me, David. There may be hope for you yet.”

She stopped, cocked her head, and studied him. “Better show me where my studio will be,” she said finally. “It sure isn’t going to have a skylight, but it had better have a window.”

Kennerly’s happy yelp attracted Martin’s attention, and he put his short legs to work tracking it down. But he was only confused when he found his parents kissing.

#

Epilog: The Garden of the Cognoscenti

After the critics have criticized, the analysts analyzed, and the historians historicized (sorry, Miss Plummer), what’s left that is meaningful without being obvious? What are we to make of these exciting years?…

Where once hung a threat of federal domination, true local control has returned. Where diversity was once a punishable offense, it is now a rewardable virtue. Where students were once encouraged to reject their parents and their teachings, they are now provided a chance to embrace them. Where ivory towers once dominated the landscape, flowers of consumerism now rise from their rubble. Where teachers held sway as dictators, they are now servants. It is a wonderful time to be a parent or child. There now exists a veritable garden of educational delights, from which the connoisseur may assemble a tasty menu for the mind. As we enter the new millennium, we can be confident that our children are better off than ever before in our history.

– James Griveny New York, May 17, 2002

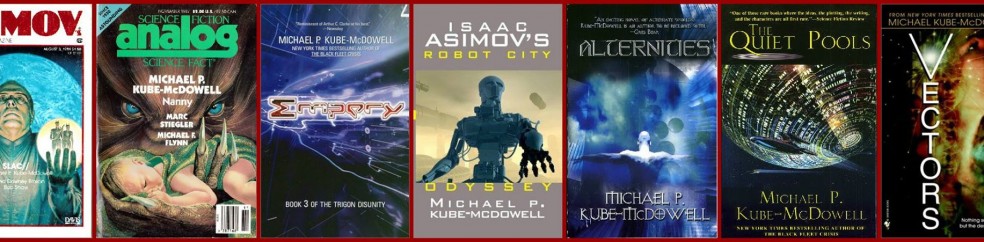

In the 1983 Locus Poll voting, “The Garden of the Cognoscenti” finished 20th in the Best Short Story category. It finished 2nd in the 1983 AnLab polling.