by Maitland A. Edey and Donald J. Johanson

(Little, Brown, 1989)

418 pp., $19.95 cloth

Where is the history of humanity written? In rocks and fossils and the molecules of the living cell, or in the pages and passages of Genesis?

A hundred and thirty years after Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, Western society is still divided on the answer. The scientific community has long since accepted evolution as a fact and embraced it as a unifying principle of biology. But some polls show that nearly half the American public rejects evolution, preferring the Christian Bible’s story of Adam and Eve in Eden to paleontology’s story of Lucy, the Taung Child, and Olduvai Gorge.

With Blueprints, former Life magazine editor Maitland Edey and leading paleontologist Donald Johanson have joined forces to try to close the gap between science and the public by recounting for the general reader what they call “the greatest intellectual detective story of all time.”

It’s as much a story about how science works as it is about the theory of and evidence for evolution, for Darwin’s seminal work precipitated one of the greatest scientific revolutions in history. Appropriately, then, Edey and Johanson chose to tell that history by focusing on the many people who made it — including Malthus and Darwin, Watson and Crick, Leakey and Johanson himself.

The result is an uncommonly personal book about science, one that highlights curiosity, discovery, failure, and triumph. Blueprints portrays the unfolding, still unfinished tapestry of scientific inquiry into life and survival on a changing Earth.

Using everyday analogies and resorting at times to a literally conversational style, Edey and Johanson highlight every fascinating advance in evolutionary science, from Lamarck’s brave speculation that living things change over time to the latest lessons from molecular biology.

Blueprints can be considered an ambassador from the scientific community to the nonscientist, saying “This is what we’ve learned. This is what we know. This is what we believe.” Because it eschews polemics and propaganda, it may even serve — as Edey and Johanson hope it will — as a bridge across the gap dividing scientist and creationist.

To the degree it does so, it will help write the history of the future. For, as the authors note, we are poised on the brink of being able to control and direct our own evolution through genetic engineering. And the better we know ourselves, the better choices we will make.

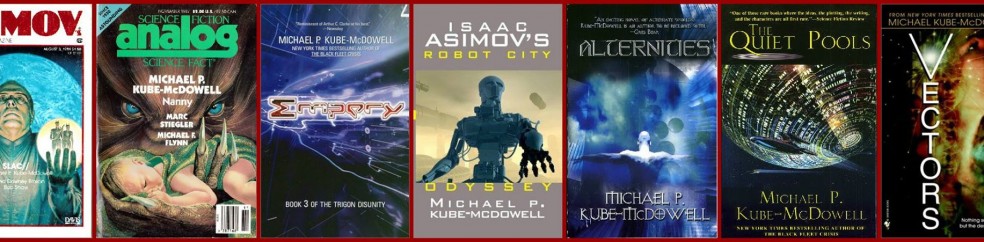

— Lansing resident Michael P. Kube-McDowell is a former science teacher and the author of the novel Alternities (Ace, 1988).